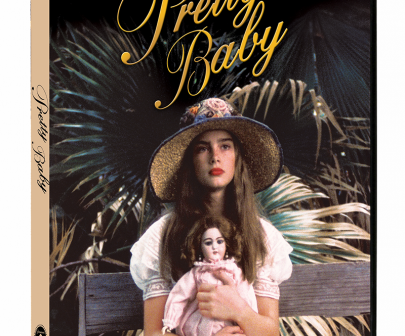

In 2020 Pretty Baby is a very difficult film to review. Made in 1978, it features an 11 year old Brooke Shields as Violet, a child prostitute growing up in a 1917 New Orleans brothel. Abandoned by her prostitute mother (Susan Sarandon) she is at one point auctioned off to the highest bidder for the right to deflower her. There’s also a couple of pretty uncomfortable nude scenes of a prepubescent Brooke, and at one point she marries an adult…in a church.

Obviously it could never be made today, but should it have been made even then?

It’s the work of French new wave (ish) director Louis Malle (Viva Maria!/Atlantic City), an individual not afraid to take difficult, at times taboo subjects and approach them in a highly idiosyncratic way that no one else on earth would, or could. His films are often so leftfield that the normal rules and mores don’t seem to apply – yet he could still attract the odd obscenity lawsuit (for The Lovers). As a result Pretty Baby is not the film you think it is. It’s not sleazy, it’s not revelling in its shocking subject matter or attempting to titillate. It’s much worse than that. Malle approaches the camera as a chronicler. There is little judgement in his lens, shocking things are given as much gravity as inconsequential moments, and this is what is so difficult to take.

The film opens on a close up of Violet’s face and what sounds like a women in ecstatic sexual bliss. It’s clear Violet is in the room, and it’s impossible not to pass judgement and feel concerned about what this young child is being exposed to. Yet all is not what it seems as Malle reveals that her mother Hattie (Susan Sarandon) is actually giving birth. Judgement is never far from the surface in Pretty Baby, though you have to come up with it yourself as Malle cloaks everything with a frivolous veneer of normality. He doesn’t tell you what to think (or even what he thinks). And that’s rare in cinema – particularly in a subject matter like this.

It’s Malle’s first American film, and it’s fascinating to think that with Hollywood dollars this is what he created. It’s a fictional story based in an elegant brothel in Storyville, the Red Light District in New Orleans. It’s a place that Violet has spent her life. The working girls are her family and sex as a commodity is the most natural thing in the world. Into this world comes a shy photographer Ernest J Bellocq (who actually did exist) played by Keith Carradine, who photographs the girls and develops a relationship with Violet who is at first fascinated by and then infatuated with him.

In most films due to her age and apparent innocence Violet would be a victim, but Malle paints her as the one character most in control while those around her are unreliable, selfish and at the mercy of their demons. Whilst this may very well be the fantasy of a middle aged Frenchman, it does challenge the familiar narrative. After being sold to the highest bidder Violet masks her nervousness by using suggestive sexualised language of a far more experienced girl, something she no doubt had seen many times. This just serves to highlight how out of her depth she seems. After the act when her mother and the other girls check on her she is inert, seemingly unconscious and they begin to panic. Suddenly she begins to laugh, tickled by the trick she has played on them. During these moments it’s impossible to breath. Impossible to imagine these as moments of play, but Violet is a child and the sexual act doesn’t seem to carry the weight for her that we expect it should. This feels like very dangerous territory.

In interviews Malle was at pains to point out that there were child prostitutes, and that child marriage did occur during this time. So because they did we should make films about them? It’s such a difficult film to reconcile. It’s beautifully shot, fascinating and contradictory. It provokes without seeming to be wilfully provocative. Brooke’s performance is simply remarkable and she looks back on Pretty Baby (nude scenes and all) fondly, as a participating in a pure artistic experience, and the film as an incredible work of art.

The normalization of these acts within the narrative though is a concern, as much as the lack of an explicitly rendered judgement from the filmmaker. As a viewer I was desperate for Malle’s take, as I wanted to be reassured that I wasn’t watching a paedophilic fantasy. But aside from a few strategic moments Malle remains resolutely neutral, and instead his approach seems to be relying on the inherent morality of the viewer – which feels optimistic at best.