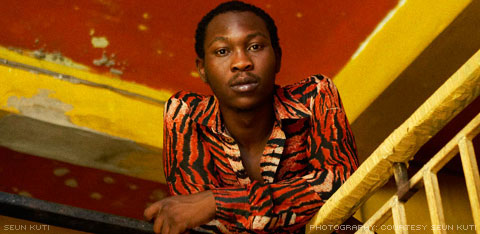

It’s hard to conceive of an individual more relaxed on the phone than Seun Kuti, the youngest son of afrobeat icon Fela Kuti and now perhaps the leading torchbearer in the afrobeat revival that’s currently sweeping the world. He fronts formerly his fathers, now his own Egypt 80, and has just released his second album the pointedly titled From Africa With Fury: Rise, another bruising up-tempo slab of afro funk, and it’s impossible not to detect a certain pride in his accomplishments.

He speaks gently, though is incredibly eloquent, equally adept at discussing politics in Africa, offering a self-deprecating swipe at himself, or reflecting upon the recent renewed global interest in afrobeat. “Yeah of course, especially with the Broadway show afrobeat has become a lot bigger, he offers.”

He’s referring to the Tony award winning Fela The Musical, which after a successful run in New York, London and Amsterdam, even went to Lagos for a week. In fact it’s still playing across the United States. Which can only mean one thing. We’re inches away from Will Smith as Fela.

“There will be a movie I think. But I don’t think Will Smith will play Fela,” he laughs, “maybe someone else. But I think they’re working on a movie.” His second album, some three years after his debut puts him at the forefront of the afrobeat revival. In his hands afrobeat feels like it has been rescued from history and is once again a vital transgressive and meaningful form of political protest. The music is of course the potent blend of relentlessly rhythmic afro-funk that Fela pioneered, yet in Seun’s hands it feels like there is so much more going on.

“I just wanted to do something new,” he offers. “That’s a mission of mine. The second album I didn’t want it to have the same energy as the first, I wanted it to have a different feel, but the same DNA of the music to keep afrobeat alive. That was on my mind you know.”

It’s an album that still feels like afrobeat, yet there are a myriad of styles and approaches coursing through it. In conversation Kuti speaks of everyone from Radiohead to Talking Heads, and as an avid music consumer it’s impossible that these threads wouldn’t find their way into his sounds. Then of course there’s the presence of Brian Eno as producer, whom he first met when Eno programmed him for the Vivid Festival in Sydney. “Brian has a huge knowledge in African music,” Kuti relates. “He went from Talking Heads and you can hear the influence of African music in his work. Even when I met him his knowledge of afrobeat was immense. It was nice to meet someone who would look at me from a different perspective. I had a good time. It was an eye opener for me. Everyday with Brian was a day where I learnt more and more about music – even my own music.”

Recording in Brazil he then took the material back to London for mixing with Eno, John Reynolds (Herbie Hancock) and Tim Oliver (Sinead O’Connor). He credits Eno for assistance with arrangements, solos, effects ‘things like that.'”I learnt more and more and he helped me open up my music,” he offers. “Because Brian is Brian Eno for a reason. This is not because he is some over-hyped man. He is a man who has real talent. I think his idea for sound is unmatched anywhere in the world. In the studio listening to the tracks he comes up with all these ideas of things we can do to improve the sound.”

Whilst the band recorded live together in the studio this doesn’t necessarily immediately translate to a great sounding live album. In fact strangely enough to make a recording seem more live often large amounts of studio trickery are involved. “You have to accept that the idea is perfect for this sound,” Kuti suggests. “I’m used to making good live music and Brian was able to make it a good live CD.”

Kuti does most of the songwriting before presenting it to the band, though there’s a policy that anyone is able to compose songs. Kuti then picks the best songs for the album.

“I think I write five songs on every album and keep the remaining two or three slots open for anyone who writes a good song from the band.” The result is an album heavily steeped in African politics, decrying dictators who steal from their people before scurrying off to exile when their people rise up against them, multinational companies out to exploit Africa, and the power of the military.

“For me this is my interest,” he offers. “I’m very interested in situations that affect Africa and the policies that affect Africa. That being said not just afrobeat music but all African music has a responsibility to represent its people to be a voice of its people. So I think that’s also in my mind when I’m writing these songs. To be honest as possible and show real love. Not selfish love of you or your girlfriend or your money or your car but the real love of your people and the real of your land. So there’s a situation that can benefit even your own children and their children.”

When I suggest that it feels like a big responsibility to carry, Kuti laughs. “I feel as long you don’t add religion to it and claim to be holy; you should be able to accomplish the rest. For me it is not so difficult to live. If you work hard and you make money you can live a life of luxury and do what you want to do. But you don’t feel a necessity to talk about that with your music as well. Because that is selfish. What your music is about should be bigger picture. Not your wealth and comfort which is what music is about these days, parties, how much money, drink, how much gold you wear. But that’s not important. We live life like that because humanity likes comfort. OK fine, but the majority of humanity can not afford that.”

Which is ironic given the populace’s preference for bling-laden performers who utilise their video clips as an exercise to demonstrate how wealthy they have become.

“Entertainment has the power to influence,” retorts Kuti, “and that is what is given to them by commercial music and there’s a lot of money backing that up. That is the lifestyle that is projected and people want to have that life. It’s not special; this is just what the industry promotes. Because if you think about the 60s and 70s when people were much more political, they were engaged in the world, they would stand up and march for everything. And music inspired them to do that. This is what the establishment realised and they’ve been dumbing the music down over the decades and now it’s about surface things.”

Kuti’s music is anything but. Having taken over his fathers band Egypt 80 after his father’s death when he was just 14 he has done the hard yards, not releasing their first album, the explosive Many Things until he was 26. At the time he spoke of not wanting to make an album until he was ready both musically and personally, as he learnt from his father the life of an afrobeat musician can be fraught. In fact he’s still the youngest member of a band he has grown up with, with the oldest being in his 70s

“Everybody has been together for such a long time,” he offers. “We’ve just got that chemistry, we’re able to do our own thing, everybody’s happy. And within the band there’s a real equality, and everybody’s able to relate what they’re thinking or say what’s on their mind without any fear of repercussions or anything like that. I think that helps.” With a relentless touring schedule, made up of fifteen members for overseas shows and twenty at home, surely some of the older guys are struggling a bit with the pace.

“No man,” Kuti laughs, “these guys are real rockers, everyone’s having a good time.” Seun Kuti treads a fine line between being his own man and honouring his father’s legacy. For From Africa With Fury: Rise, Kuti has added his father’s Yoruba name Anikulopo to his own, though has also enlisted the skills of Lemi Ghariokwu, a man behind some of Fela’s most iconic album covers. And whilst stylistically Seun differs considerably from his father, with a huskier vocal timbre, and a more youthful earnestness, there are some things that Seun believes are sacrosanct. Such as playing at the home of afrobeat in Lagos, Nigeria, Fela’s infamous shrine.

“We play at the shrine every last Saturday of the month,” Kuti reports. “Sometimes we can’t make it, but most times we do. We’re a live band and you have to play. The only way to stay sharp and on point is to play live. And also it’s the shrine. Afrobeat has to be at the shrine as often as possible.”