There is an elusive quality to the music of Max Richter. Since the release of his first solo album Memoryhouse in 2002, on the BBC affiliated Late Room label, his music has been characterised as emotive, nostalgic, imaginary, cinematic and even “post-classical’. Recorded for Fat Cat, his most recent albums, The Blue Notebooks from 2004 and last year’s Songs From Before take passages from the writing of Kafka and Murakami respectively, weaving spoken word excerpts through aching orchestral instrumentation, piano and ambient recordings. These descriptions may suggest some kind of kitsch sentimentalism to the cynical reader but Richter’ music disarms any such assumptions; it’s hard not to be transported by his thoughtful and immaculately crafted sound-worlds.

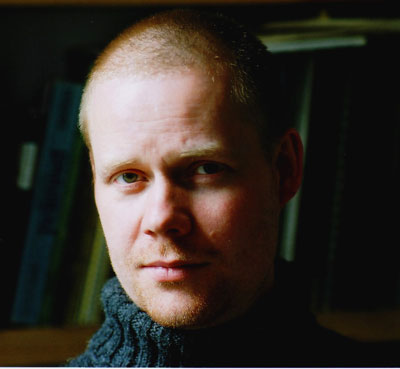

Born in Germany and raised in Britain, Richter’ diverse career has seen him perform as part of the acclaimed piano sextet Piano Circus, collaborate with artists like The Future Sound of London, Roni Size, and Vashti Bunyan, as well as work on film scores, installation and gallery works. This diverse career was anchored with formal training as a composer and pianist, having studied at the University of Edinburgh, the Royal Academy of Music, and with Italian composer Luciano Berio. I caught up with Max in his home in Edinburgh to discuss his latest album, his compositional process and his current listening tastes.

An intriguing aspect of Songs From Before is that it contains plenty of threads from The Blue Notebooks. It feels like quite a different album, but it utilises a similar approach, with spoken word fragments of text (this time from Murakami as opposed to Kafka). In terms of tone, Songs From Before is a different beast, altogether grainier and somewhat incongruously, for the music contained within, more punk than its predecessor. Max takes up the commentary on these big issues; “I was definitely looking for that ‘grain’ in this record. I guess I think of the records as being joined up, a body of work. They are, to some extent, an arbitrary slice, because the way I work is to just keep writing and recording all the time. It’s like taking a collection of concepts and sketches that are floating around at that moment and condensing it into a record.”

“I’m fascinated by Murakami; I think he’s a really interesting writer, he has a magical way of dealing with very ordinary things. You think you’re reading about something very ordinary, but there’s something very affecting and serious going on underneath. I’m fascinated by this ability to capture the nature of things without directly addressing the “big issues’. One of the things with the new album is how the pieces came to be made. With Memoryhouse and The Blue Notebooks, I was aiming for very perfect, finished pieces. In Songs From Before I was looking for something a little rougher maybe. Something where the pieces themselves weren’t so perfect that they kind of kept you out a little bit. I wanted the edges to show a little more – so I guess it’s a punkier kind of record.”

The fragments of narrative that pepper the last two albums have enthralled me. On Richter’ latest, Robert Wyatt’s inscrutable vocalisations transform Murakami. Actress Tilda Swinton’s readings of Kafka and Czseslaw Milosz augment The Blue Notebooks. They’re not describing things or events; they’re more like reflections, or capturing moments. Its almost as if they capture something fragile, a fragment; it seems to fit so well with the way that I interpret Max’s work. “We all have moments in our daily life, instances of a kind of magic, in an ordinary way, which I believe is special. I’m really interested in the poetry of those moments and how they come about in a slightly random kind of a way. Musically, I’m interested in those things that have a narrative, a storytelling quality and some sort of pure magical musicality; hunting those down and trying to present them.”

Richter’s work has been described as “emotional modernism’ or an “imaginary soundtrack’. It seems as if these descriptions fit with how the composer himself describes the feeling of his work. I was curious to discover Max’s reaction to having these kinds of labels attached to his work; “I don’t really mind what people say about it honestly. One aspect of making music, or creating anything really, is in making it, you’re trying to find out what it is. It’s kind of interesting for me to hear what people say about it because I’m not really the best person to judge it. I make this stuff, but I’m so close to it that I can’t have a birds-eye view. In a way, people who are coming to it fresh have more interesting things to say about it than I do! If that makes any sense…”

“I don’t believe that critical observations on my work have changed the way that I perceive my music. Like everyone who makes things, who does music or any kind of creative stuff, it’s an outcrop of an obsessive compulsion, so it’s not like I have any choice about it, really. At the same time, it’s almost like I’m a butterfly collector; I find these sounds and then I try to capture them. Even though I try to plan everything meticulously and I entertain all kinds of schemes in my head, it’s a bit more random than that. In a way I feel that I partly come at it from an outside perspective; I’m really just following the material. I make a fragment or a sketch in the computer, or play something on the piano and then it’s a question of finding out how that can stand up as a sound, as a piece of music, as an environment. I do use improvisation. But to be honest, I use everything I can get my hands on, whether that be found sounds or recordings, the properties of a particular bit of kit, or playing at the piano, even just wandering around staring out the window. I use anything that I can lay my hands on to make pieces.”

So, despite Richter’s background in classically trained composition and performance, his working methods differ little from the bedroom auteur embarking upon his or her first recordings. Most bedroom musicians in the new millennium start on electronic equipment of one type or another, and I was interested to know when Max began to utilise electronic equipment to mediate his creative process. “I’ve come full circle with it really. In my teens I was building analogue synths, so I had an interest in early electronic music. I gravitated from there into electronic music with a more academic bent, Stockhausen and people like that. Then I went down the whole academic music route, with the degree and postgraduate stuff, composition studies and I was also working as a performing contemporary music pianist in Piano Circus.”

Max’s tenure in Piano Circus, which he co-founded as an outlet to play Steve Reich’ “Six Pianos’ was where, inexorably, over a decade, the skeleton of the Richter sound that has been captured on his solo albums, started to take shape. “With Piano Circus we started to incorporate live electronics. Our staples were things like the American minimalists, but we were playing Brian Eno, Future Sound of London, and things like that live as well. Then it all started to join up, but in a way those two cultures have always run in parallel for me.”

Richter has also undertaken numerous audio collaborations in differing roles, as a performer, composer and producer. One of his earlier collaborations was with The Future Sound of London on their 1996 album Dead Cities. “Dead Cities is a really interesting record. That was at the beginning of my time with Future Sound and initially on Dead Cities, I just jammed a bunch of stuff together one night. They just pressed “record’ for a couple of hours and I played the piano, it was as simple as that. The track “Max’ was the outcome of that. It’s interesting because there are two strands of improvisation in that track, one of them is my piano part and the other is the sax. These are actually two completely independently recorded performances on different days, put down without hearing one another’ performances. Gary and Brian just sliced and diced them until they fitted together. On their next record (2002s The Isness), it was a rather chaotic three year period, I got much more involved on the production side, working together with them in a whole variety of ways. The interesting thing was that I spent a lot of the time on the phone to Gary, who was in India at this stage. It was a weird, collaborating over the telephone line, where he was literally sending mixes down the wire. That record took a strange, chaotic shape over a long period, it was a wild ride.”

It’s great when collaboration is given time and space, or perhaps distance to develop in its own way. Max recently produced Vashti Bunyan’ “comeback’ album Lookaftering. I was a big fan of her debut album from 1970 Just Another Diamond Day, produced by the fabled Joe Boyd. Upon initially hearing Lookaftering, the difference in tone was startling. Vashti commented in an interview that she credits Richter with the overall feel of her second album. “As a producer, it’s like being a midwife, facilitating the birthing role, and its kind of, whatever that takes. Sometimes it’s “push-the-faders’, and that can be all right; in the case of Vashti’ record it was certainly more organic than that. The process for Lookaftering was the best part of a year, it was a weekly session in my studio where we would just shuffle around ideas and try sounds and sketch out stuff, and really get inside the material. The arrangements and the way that the music was presented evolved continuously. By the time we were recording for real, pretty much every single note had been decided and thought about very carefully between the two of us.”

Lookaftering sounds so much more spontaneous than Max describes, particularly on the sublime “Here Before’, with its washed loop sound setting the overall tone of the album. “That’s an intervention of mine that I made quite late on, that was a bit of a liberty really. I love that track! We were nearly finished and we’d done all the vocals and everything. I just wanted to really do something with her voice, because it has such storytelling power. Why are there no backing vocals on the record? Why haven’t we done something with it? There are the five Vashtis’ on that track, there is the main vocal and two either side, singing in a round, a traditional folk structure. The lyric talks about looking backwards, so everything, all those dubs, are going backwards. I just thought, let’s try and push it a little further than just this acoustic sound. I was slightly nervous of playing it to her actually, because we had presented the rest of the material more simply and plainly. She was thrilled when she heard it, which was a relief, because it was a unilateral move on my part, which I was ready to have thrown away.”

The cliche of the “imaginary soundtrack’ has a long pedigree in the instrumental diaspora. It’s almost insouciant journalistic shorthand, a signifier for certain traits that may be discernable, if only the listener ascribes specific meaning to the music. But describing Max Richter’ work as having a visual element is not just poetic license. His collaborations have often crossed into the realm of related artistic disciplines. “The Derek Jarman project; it isn’t really a soundtrack. I received a commission to write some music for film to be played live. I was scratching my head thinking about an existing film that I’d like to work on and I couldn’t immediately think of anything that really grabbed me. A friend of mine happened to know of the existence of these amazing Super 8 films made by Derek Jarman during the 1970s. Some of them are diary pieces, some of them are home movies, some of them are sketches for his later feature films, there are even art pieces for display in a gallery. It was an incredible experience to go through that collection containing hundreds of films, and make an assembly that made sense as a performance. I composed music that would stand alongside those, so it’s not really a film score, but a piece of music and film where sometimes, for example, the screen is blank and the music is just playing and sometimes it’s just the film. The music is all live; it has been really good fun to do it, a lovely project, Jarman’ films are incredible. People are amazed by the film and have been responding really positively to the piece. There is a kind of alchemy that happens on stage where the music and the film are really speaking to one another.”

“I’d like to release the Jarman score, I’m very pleased with how it’s turned out. Apart from that, I’m working with a fine artist called Darren Almond, on another image and sound piece that will be coming out by the end of the year. I’m doing a film at the moment, an animated documentary for cinema made by an Israeli director. I’ve just collaborated on what is really the first American film to look at the Iraq war. It stars John Cusack and is called Grace is Gone; it’s been a real pleasure to be involved with that. There is a concert I’m playing at during February in Holland or Belgium, where we have a filmmaker called Matt Hulse , who made a full-length film for The Blue Notebooks. Again, it is Super 8 film, which we do in a live setting. More traditionally, I have done some film scoring work over the last couple of years that’s a different kind of discipline, because music within a feature film context has very specific kinds of functions.”

Knowing that Max spends most of his time in the studio, and that many of our readers are technically-minded, I felt obliged to enquire about the Richter studio set-up. “I have a Mac running Logic with the VSL orchestral library and thousands of plug-ins, that’s the recording side, although I use it really only as a sketchpad, the actual recording for the albums, I always do on tape. I have a couple of studios where they have what I like; a two-inch 16-track and an old MCI desk. It’s a warmth thing; I’m trying to make records that sound like records, so therefore I only use real instrumentation in the studio. I think our idea of what a record sounds like was shaped way back, so I use that equipment which makes that sound. It’s quite simple really, it’s not really a technical question for me, it’s simply a question of feel. I love all that wonderful stuff you get for free when you’re mixing off tape, like the natural compression. It’s just so much easier and more fun.”

Always curious to discover what fires-up the creative juices of an “emotional modernist’s in these musically cross-pollinated days, I had to know what had been getting a caning on the Richter stereo. “I listen to a lot of classical music, going way back, I always listen to Purcell and Bach. I’ve got Sufjan Stevens, Burial, Skream, Beirut; you know the Gulag Orkestar thing. There’ Joni Mitchell lying there, lots of Mozart, Dutch composer Louis Andriessen, all kinds of stuff. There’ The Go! Team, the original Go! Team album, before they replaced all the samples.”

I purchased Songs From Before at the same time as Jóhann Jóhannsson’s IBM 1401: A User’ Manual, and it had happened previously with The Blue Notebooks and Englabörn. I just had to know if Max had any of Jóhannsson’s work; “I do, in the car I’ve got Virðulegu Forsetar which is a great record, the brass one you know? Amazing. I think we’re tracking each other; it’s weird isn’ it? We always seem to release records at the same time. There’s something going on to release records at the same time. There’s something going on!”