130701 is a subsidiary of the legendary UK label Fat Cat Records. Formed out of a contractual necessity fifteen years ago in 2001, 130701 has recently come out of hibernation with a new lease of life, energy, and a rush of new releases from a new wave of young artists. I caught up wth Dave Howell over an extended cross-continental email exchange, just as he is on the verge of releasing a fifteenth anniversary collection.

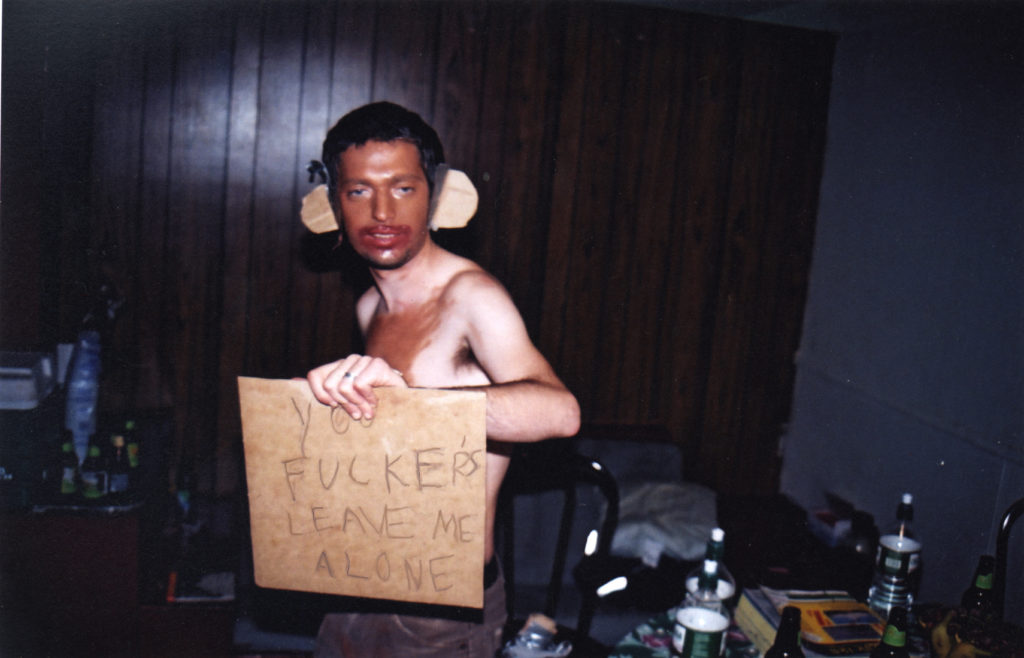

Dave Howell, 130701 label boss, backstage

SC: I remember back in 2001 when you were travelling in Australia for the This Is Not Art and Sound Summit festival and you gave me a promo of that first 130701 release, the Set Fire To Flames’ Sings Reign Rebuilder album. I don’t think I really started thinking of a 130701 aesthetic until after Max Richter’s The Blue Notebooks. How did this all develop? And given the misunderstood role of a record label in these modern times, what exactly is the role of a ‘sublabel’?

DH: Wow – good memory, Seb! That must’ve been exactly at that time, as the album came out in October (2001), and I can vividly remember we flew out to Australia 2 or 3 days after 9/11!. There was no aesthetic, no big plan for what the label should be. It was in no way preconceived. We just set it up purely for that first Set Fire To Flames release. As you know, SFTF came out of that quite politicised Montreal scene and included members of Godspeed You Black Emperor, Fly Pan Am, etc. One of their strict stipulations when we started talking with them was that they wouldn’t tolerate any link to shady corporations or to the military-industrial complex. I guess you’ve seen the back cover of GYBE’s ‘Yanqui UXO’, right? Anyway, when we started talking with them we were in a joint venture with a bigger indie label, PIAS Recordings. The band did some digging and it turned out that PIAS were themselves tied into a venture with a larger business partner, and somewhere or other, that company had deals with arms manufacturing or some area of the military-industrial complex. It’s a long while back now, so I can’t recall exactly, but that was the upshot. So we set up 130701 to operate completely independently from that and we named the label after the date it was created on. I think by the time the release was ready, PIAS and that other company had already split anyway, but the imprint stuck.

Set Fire To Flames

It was such a great fucking opening record to put out. I mean, just this incredible, massive labour of love all round, from the recording process through the editing, the artwork, the insane packaging, the mastering, writing the PR sheet, everything. A year or so later we got sent a record by Sylvain Chauveau, Un Autre Décembre, which I love, which just seemed like it would fit alongside SFTF, so that became the second release. I can’t even remember how the artwork came about for that one, but again it was a sort of grainy monochrome photograph. The second SFTF album came another year later, which again was another beautiful Michael Ackerman pinhole photo, so I think by that point whilst we didn’t have any clear vision of how the label might sound, there was the beginnings of the visual aesthetic. A few months after that, we hooked up with Max Richter and I guess from Sylvain’s piano and SFTF’s use of certain classical instrumentation, we corralled him into 130701 and again used a B&W photo by a friend of ours in Brighton. So I think you’re right, that’s the first point at which we really began to start feeling some sense of what 130701 might be.

I think any of those records could actually have fit on FatCat. The parent label was always really broad and made a virtue out of pushing those boundaries, but I wanted 130701 to start to have some clearer raison d’être. And it just happened that fell into place around the idea of classical instrumentation being used for new ends and merging with new sounds and noises. And working with interesting, progressive artists, and setting really high quality control bar. I wouldn’t call 130701 a sub-label any more – it sort of drifted along for a number of years without the need to be releasing a load of records (because we were all so busy working on all the artists that were going through FatCat and there just wasn’t actually that much time left to really develop 130701 as a bigger concern). So it just existed with some greater sense of its own identity, just dripping slowly, infrequently on alongside this multi-headed torrent that was FatCat for quite a while. I dont think many people really made any differentiation as to what 130701 was, or really saw it those artists as being outside of FatCat.

I think from Max Richter onwards, there’s a greater sense of coherence with Hauschka and Johann Johannson and Dustin O’Halloran sitting together fairly neatly. At that point, I think those 4 or 5 artists start to look like a seriously strong roster and I think 130701 started to really feel like it is its own force. That unfortunately got cut down pretty quickly, but I think again right now, the imprint is feeling like it is its own thing, it has its own identity, sense of purpose, and 130711 is extending itself again.

SC: Looking back I can see that 130701 releases act almost as signposts of where things are heading in the subsequent years. Richter first, then Hauschka, Johannsson, O’Halloran, Chauveau – its become like a roll call of ‘celebrated film composers’. What has changed both in terms of the broadening of what ‘contemporary classical’, and in terms of film soundtracks?

DH: Well, I’m not really sure about the film soundtrack side. It’s not something I follow hugely, but for sure there was a point that started shortly after Max’s ‘The Blue Notebooks’ and ramped up really rapidly, where if you were in the UK and turned on the radio or the TV anytime in the evening, you were almost certain to hear his music being played as a sound-bed somewhere most nights. It quickly reached a point where it felt like it was becoming part of the soundscape [of the time], and was relentlessly used in the media as a shorthand for certain kind of ’emotionality’.

Max is brilliant and he has very strong interests across different creative media (dance, film, art, literature, opera, photography), which you can hear in his music from the get-go. So I think given those two things, it’s fairly natural that he should be one of the go-to people that directors would want to work with. But we didn’t sign any of those artists with a view to them being ‘celebrated film composers’ and really, Hauschka’s only fairly recently started entering the film world.

As far as the ‘contemporary classical’ angle, it feels like we need to have some kind of term to help outline the kind of area we are talking about – we went with ‘post-classical’ a long while back and it kind of stuck, though I’m not really comfortable with any of the genre terms. When we started, none of us here had any knowledge of classical music. Some of us had checked out some of the minimalist and avant-garde stuff from the 50s onwards, and might have some dim understanding of Satie etc but it was patchy at best.

There was one band I was really into that felt like they were out on a limb on Touch & Go through the mid-90s called Rachel’s, from Louisville. That was the first time i’d really heard anything of a kind of modern take on what you could call ‘chamber music’.

But all through that time we first started working on 130701 it felt like there was no connected-up scene for things like Sylvain or Max. It was just a small bunch of people working away mostly in isolation and mining their own little seams and niches. There was nowhere in the record stores where you’d find all this indexed together and there wasn’t anywhere it was grouped in the press either.

A couple of years after we’d released Max’s first record, you could see a few other labels beginning to work in that area – Type, Erased Tapes, one or two others. And there were a few promoters like Arctic Circle over here who quite early on started putting on these artists. As some of these different strands started to stick, then it gradually started to come together more and more, and it was clear that there was some sort of market for this type of music and certainly that there might be a lot of possibilities for sync [licensing for TV and film].

I’ve definitely felt like there were moments when things were really lifting off – around 2012 when we had the Transcendentalists tour, and then last year, with Max’s Sleep and with the huge Nils Frahm/A Winged Victory show at the Royal Albert Hall. That definitely felt like some kind of tipping point had been reached. The floodgates have opened and there’s so much more receptiveness for the genre. I’m getting sent stuff almost daily now by pianists, [unfortunately]so much of it sounding really bland and derivative.

SC: It must be good to see new performance opportunities opening up for all these artists. Have you found that new types of venues have opened up to you?

DH: I’ve been to pretty much all the London shows from the 130701 artists. Quite a few of the shows have been in pretty nice black box cultural institutions like The Barbican & Southbank, but there’s also been quite a lot in churches. The Union Chapel in London is a regular place where I think I’ve seen most of the artists play at some time or other, but there’s plenty more church shows I’ve been too. I think those spaces lend themselves really well to this type of music. both acoustically and architecturally. It’s a good fit.

When I remember right back to the start of FatCat, nearly 20 years ago, there were always interesting places available, certainly in London – I can remember going and checking out synagogues, disused tube stations, churches, warehouse and industrial spaces, cinemas. I just think the church or theatres or cinemas seem particularly good fits for more classically-rooted stuff. It’s quieter music, and audience-wise it’s probably mostly people who are a bit older. It’s not like people go and get hammered at the bar and want to jump around, and this kind of music wouldn’t really work at a rock venue like the Garage or wherever. So it makes sense to utilise those sort of venues that allow for more respectful/reverential listening, that are seated, that allow or suggest a heightened sense of focus.

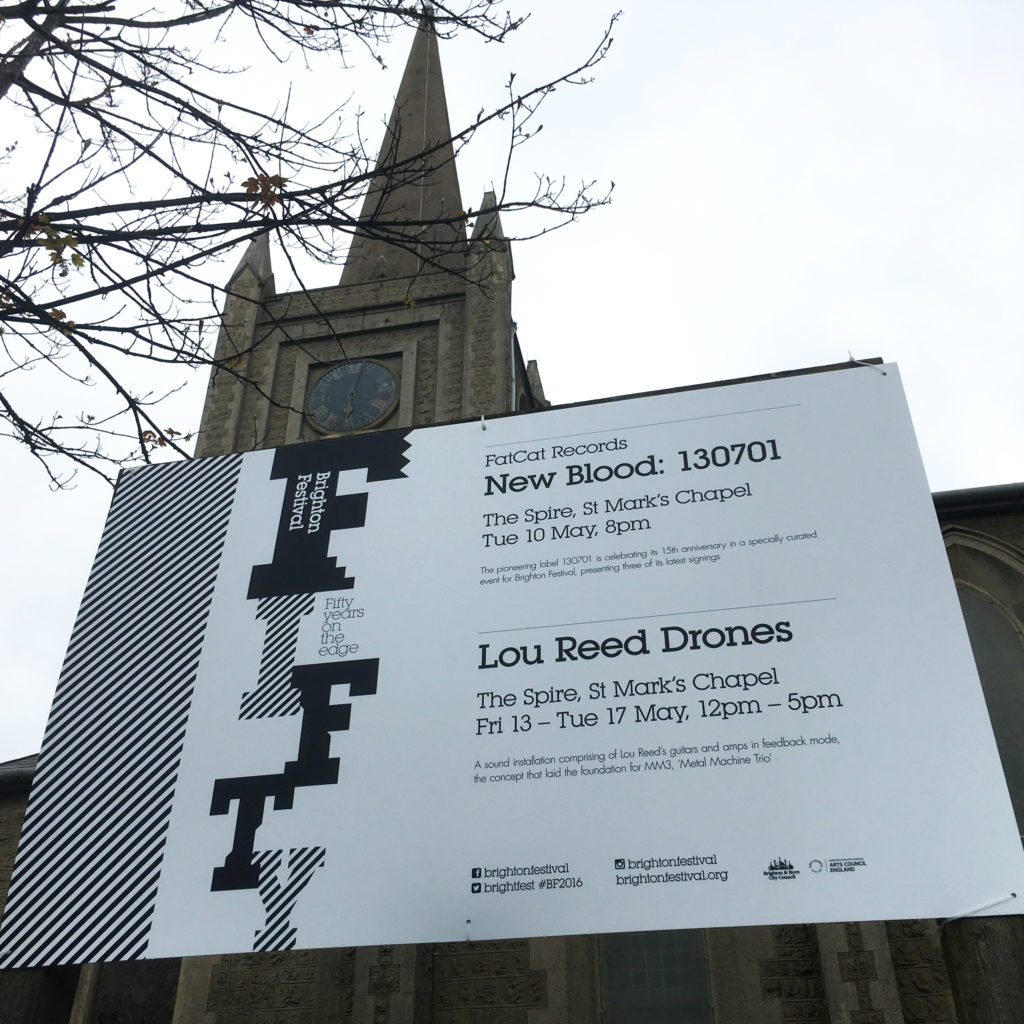

We were lucky enough to be invited to put a 130701 anniversary showcase on as part of Brighton Festival. Which was kind of a risky show for them to agree to cause it was three fairly new artists – Dmitry Evgrafov, Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch and Resina, none of whom have much of a profile and who between them have only ever played a total of 6 or 7 shows.

We managed to pretty much sell it out (at 300 capacity) and the artists all played really well. It was a really nice old church in Brighton, right on the fringe of things and somewhere that’s barely ever been used for shows. As it was a festival production there was a bit of a budget and so the sound was great and we spent a lot of effort getting the space looking really special. I got my best friend who’s a projection specialist involved, so we created these wraparound projections behind the stage and down the sides of the venue, and made the whole thing look pretty impressive.

SC: I’m sure this is a bit of sore point but it feels like Fat Cat gets burned by major labels snapping up artists that you’ve worked hard to develop and work with. First Sigur Ros and now Max Richter. Fat Cat has always had a great A&R sense! Are there any lessons for other independent labels that’d you’d pass on from these experiences?

DH: Well, like most of those artists, Max was out of contract, but it also came after we’d been through a particularly tough time. In all fairness, he gave us the opportunity to match the offer Deutsche Grammophon made him. I don’t resent him moving at all. He’s done brilliantly and it’s turned out to be a good move for him and he deserves the increased attention.

When any artist gets to that level where they become of interest to majors, it’s always a struggle. We do have the set up, the backing and the networks in place to be able to work with genuinely big-selling artists but our perceived niche, I suppose, is that we find stuff very early on before anyone else does, and then work them to a certain level or stage in their careers.

I mean, it’s often a drain, but we’ve always listened to every demo we’re sent, which is probably a bit unusual for a label of our size. I know most labels ask not to be sent demos and will just chuck them straight in the bin, unopened. We used to always listen and reply to every single thing we received. It’s harder now – we just don’t have the time to respond to things unless it’s something we like, but everything gets listened to and we’ve discovered a ton of amazing, sometimes pretty successful stuff through demos – Twilight Sad, Mum, Frightened Rabbit, We Were Promised Jetpacks, C Duncan, all those came that way; on 130701 it’s the same story with Dmitry Evgrafov, Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch, Resina, and there are others we’re looking at signing from demos at the moment.

We look where others dont and find stuff really early and try our best to work it well. Sometimes it goes fantastically well, but there’s way more misses than hits i guess. We usually sign artists on three album deals, so by the time of that third album and the deal is up, that’s when – if it’s gone really well – the majors or bigger indies step in. We haven’t always been in a position where we are able or willing to match their offers. It can be really frustrating. Short of trying to tie people down to bigger contracts, I dont really know what you can do. You still have your back catalogue when the artist leaves, so its not all bad.

SC: Recently I’ve been asking every label I speak to about the realities of staying independent. I was reading a somewhat depressing interview with Sami from Fonal where he is talking about the floor collapsing from under the label as consumers shift to streaming.

DH: Ha – Sami is a good friend. I have just about every release he’s put out I think. He runs a great label and I love his energy and what he does. He’s a diamond.

I spend such a huge amount of time working with artists, developing campaigns and trying to get the records sounding and looking right, and plenty of stuff going on around them. That’s sort of my end, my main concern. Of course I would like everything to sell really well and be successful commercially, and I guess if I had any ownership of FatCat or was running my own label I would take a lot more care and interest in it. I care a lot more about a record being some kind of creative statement and being as good as it can be than whether it actually sells well!

It’s a vastly different marketplace and industry from when I started out. There’s some great things about digital streaming. I have a Spotify subscription and – whilst there’s stuff I dont find on there – I think it’s a brilliant tool for filtering and discovering music, for sifting the wheat from the chaff.

I’m old school though in that I still ultimately want to own the musical object, to actually have the ting to hold and to feel the packaging, read the notes, pore over the artwork. I love that vinyl confounded all the predictions and has had a proper resurgence. It’s a great format and I can’t imagine ever not wanting to own records and keeping the collection active. But yeah, streaming is definitely the thing now, and I guess there’s a generation of people who’ve grown up not feeling the need to own the physical things and, worse, expecting not to actually have to pay for the music. I do like bandcamp and actually when I buy records online, that’s usually the place I wind up – I like the knowledge that the money is going to the artist or the label, rather than other conduits taking the bulk.

SC: I remember when FatCat put out that compilation of ‘best of demos we’ve been sent’ and eve back then there was a sense that the world for independent labels was expanding and demos were being sent from all over the world. Now, I expect, it is even more global. How do you filter as demos have shifted from physical to digital (and the resulting exponential increase in quantity!)? How have you found dealing with artists who are geographically distant? How important is the face to face?

DH: We get stuff from all over. It doesn’t matter where it’s from everything is judged on the same merits. The quantity we receive has ramped up – I probably listen personally to anything between 3 – 10 demos every day. There’s a ton more that are sent in that other people filter out before they get to me or to the other A&Rs at Fatcat. I mean, probably 60% of what we’re sent is just crap or inappropriate stuff that’s just sent with no thought for what sort of stuff we do – you know, mainstream R&B and pop and all sorts of stuff that we would never touch anyway. So that stuff is easily just filtered and deleted out straight away, but it’s still taking up someone’s time.

Of the stuff that makes it past this stage, I think you can usually tell fairly quickly within a few minutes wether it’s something that demands further attention, or is maybe a bit too derivative or not quite there. I sort of accumulate little clusters of things that I might then listen back to again in full and the stuff that sounds ok from this then you keep dipping back into over a longer period and work out if it is something you really are interested in, then you might start digging a bit into what it is, checking their web presence, getting in touch and asking a few questions of the artist.

Sometimes when there’s stuff that sounds close you just stay in touch with the artist and give them advice and keep tabs on them and maybe somewhere down the line they reach the point where they’re ready and you start doing stuff. It has to be a right fit for us, has to feel like the right thing and not like you’re just repeating things you’ve already done.

I always like to try and find people who have a good holistic sense of what they are doing – musically, visually, creatively. And it helps if it’s something that translates into a live setting and they are able to handle that side well, are a strong performer.

I’ve worked with a lot of artists from far flung places, where it’s just impossible to meet them before you start working, sometimes ever. In general I’d say yeah, it totally is best to meet people face to face and be able to have that time hanging out and understanding each other. But you can build strong relationships via Skype and phone conversations and email. these are way more connected times now than we had when we started FatCat and were writing and posting letters to people! It’s all pretty easy really.

SC: Now you’ve got a whole new stable of artists, a second wave, what are the expectations from these younger artists like Dimitry and Emilie for whom I expect there is no memory of pre-napster/pre-internet music?

DH: I would guess they all hope to sell a decent amount of records and to be visible as an artist in the right places, be acknowledged alongside their peers, to get the odd sync and to be able to exist as an artist and get to a place where they are ultimately working on their own terms and earning some kind of living out of it. I never tell people we’re gonna sell X amount of their albums or make them big stars and that they’ll be able to quit their day jobs.

All you can do is work with people for the right reason, because you see something in them and believe in their music, their creativity, and you try to work with them and put good teams in place around them and represent their vision the best you can. Sometimes things work out really well and sometimes they don’t. And some of my favourite releases, the things I’m proudest of, are things that went almost totally under the radar and sold nothing, got next to no press. It’s subjective of course, but sales and press are no index whatsoever of quality. Getting success is a lottery to a certain extent. Some artists have big ambitions and are never happy and see the grass is always greener elsewhere, and some are just really happy that you’re putting their records out and seeing that you’re trying to do the best you can and that you understand them and have a cool creative working relationship.

SC: What’s the vision with this new generation of artists you are releasing? What is exciting you about their approach?

DH: The current process has been to rebuild and kick-start the label almost from scratch, from a blank canvas of having next-to-no-roster. So on the one hand we’ve been trying to build up a new roster and to get enough releases out there (this has actually been our busiest ever year with 7 albums and 5 new signings), whilst at the same time trying to keep that quality control high and only bring in things we think are at a really good level. And of course, the agenda now is in part trying to respond to whats becoming a bit of a saturated environment for this type of music and try and stretch the label a bit.

I get sent a ton of piano/string-based material, and a massive amount of it sounds really familiar, if not downright derivative. I know this is the way when any band or sound becomes popular – at FatCat we had the same thing with Sigur Ros, then Animal Collective: a year or two after the record gets popular you get flooded with demos from soundalikes.

It would be easy now to just shore up and pick up a whole bunch of artists who are sat in that zone of piano-strings composers using similar melodies and approaches and just push the sync side of things and sit comfy. I’m trying to look beyond that and find the stuff that doesn’t easily fit in, the stuff that genuinely has its own voice and integrity, its own unique spin on things and something purposeful to relate. and of course trying to present it all in a strong, coherent way. That would be my curatorial vision – it might be a very opinionated and maybe others will disagree, but those are my beliefs and that’s what i’d like to try and do.

I want to keep the label feeling adventurous and vital and to keep it expanding itself. I think these new acts we’re now working with are all interesting artists that have stacks of potential and all have pretty varied approaches, and the only thing that really unites them all is that they’re on 130701.

What’s exciting for me beyond the fact that we’re picking up a number of new artists from early on in their careers (Resina, Olivier Alary and Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch will all be debuts, and I’ve always enjoyed the journey of working things from scratch) is that – probably truly for the first time – there’s a hard focus on 130701. I mean, I’m not really working on anything else on FatCat at the moment.

For the past year I’ve just been putting everything solely into 130701, trying to look back at where we’ve been, where things are at currently, and starting to look at pushing a few different angles away from what might be expected – finding some things which are getting away from the piano, from the string quartet. Also, the 130701 roster been predominantly male up until recently and it’s good to have some female energy on board now, with Resina and Emilie and one or two others I’ve been in talks with.

I think Ian William Craig might seem like a bit of a curveball for us because it’s moved totally away from that notion of classical instrumentation being used in new ways (which became the ethos of the label), although his early material is fairly based around piano. I think maybe in future some time he’ll try and do something that is more orchestrally-based as source (which idea is really exciting to me) but i love the idea of a classically-trained vocalist (and his voice really is stunning), twisting and warping, duplicating and distressing himself through tape processing. And in a way, Ian is looping back to that first Set Fire To Flames album and sounds probably closer to that than anything we’ve done since, so it feels like some kind of nice return.

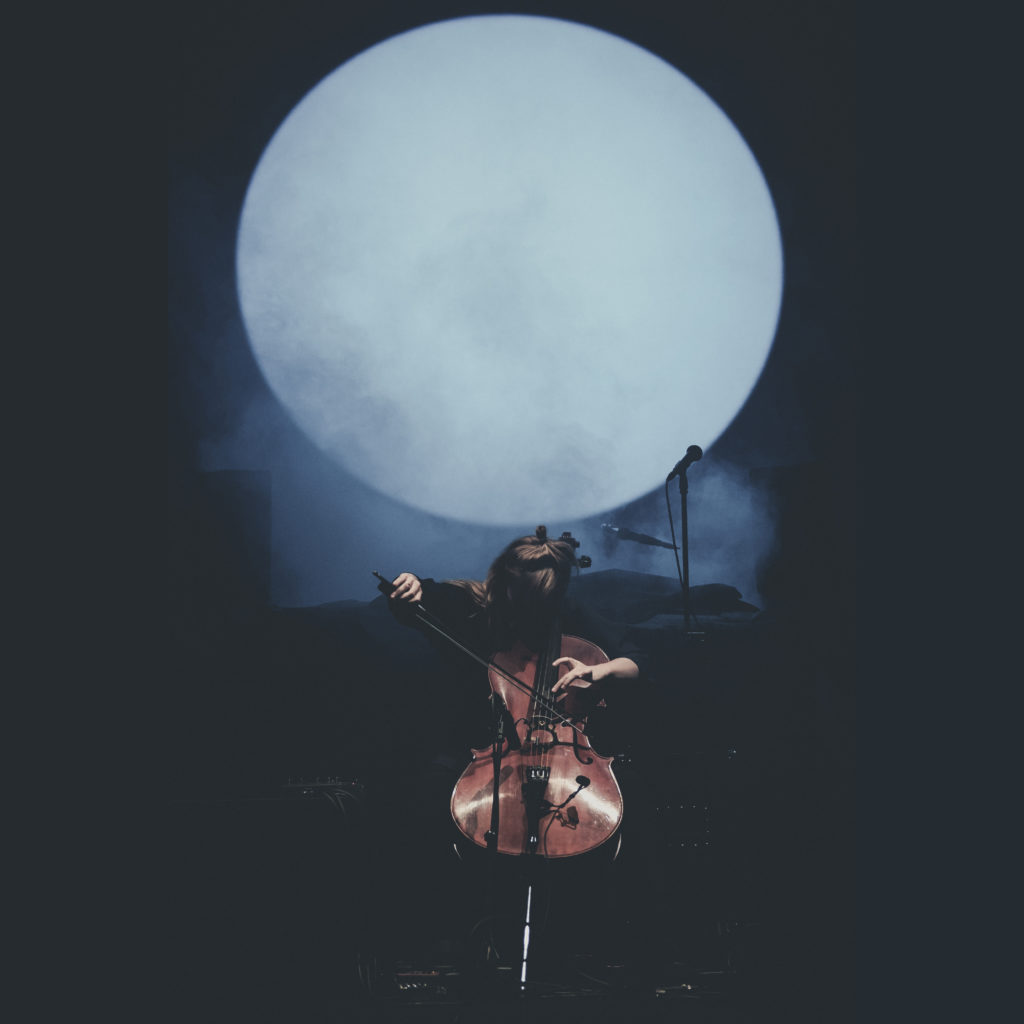

Resina live

Likewise, Resina is someone I’m really excited about who also pushes the envelope a little. She’s a cellist, but uses the instrument a little unconventionally and improvisationally, and is exploring an area closer to the likes of Richard Skelton or Colin Stetson (incidentally, both people I hugely admire and tried to get records from) than to the sort of regular chamber role I hear the cello used in. She’s a stunning live artist and I think someone who could fit a number of different contexts and have a very bright future.

There’s half dozen other artists i’m talking to so it feels like a good time to be growing again and to be reacting to the environment we’re in and trying to reposition ourselves. I don’t want the label to lazily tread water or to be easily defined and pigeonholed. I want us to stay fresh and relevant and to find artists that can push different angles and take us into different areas. Of course we also have to try to get that balance right between being creative and selling records, making ends meet, and it not being 100% risk-based.

130701’s fifteenth anniversary compilation, full of exclusive tracks, is out on July 15; and new releases – Ian William Craig’s Centres, Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s Like Water Through Sand, and the expanded version of Hauschka’s Room To Expand are out now.