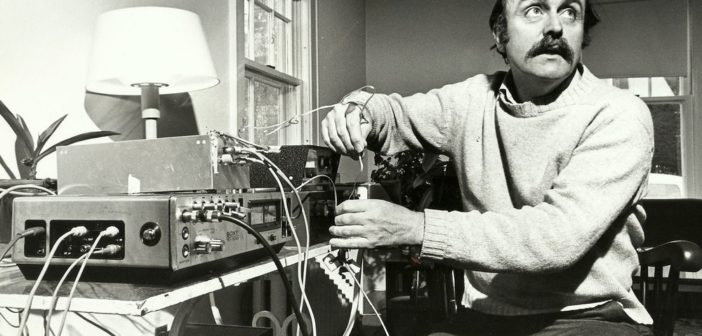

Alvin Lucier has died, aged 91. An integral part of the American experimental music scene, he was performing and fulfilling commissions for music through his 80s. Born in Nashua, New Hampshire, Lucier was a founding member of the Sonic Arts Union (1966-1976) alongside sonic explorers Robert Ashley, David Behrman and Gordon Mumma. He studied composition and music theory with Lukas Foss and Aaron Copeland, and a Fullbright Fellowship in Rome led to his first experiences of more experimental practices – starting with an influential concert featuring John Cage, David Tudor, Merce Cunningham and Carolyn Brown at La Fenice Theater in Venice. Most of his early recordings were released on Mimi Johnston’s US label Lovely Music Ltd, but his prolific output was also released on over twenty five different labels, including Mode Records, Black Truffle Records and WERGO.

Lucier’s work explores the nature of sound as an inherently musical material: the resonance of spaces, the relationship of electronic and acoustic sound, field recordings, tuning and atmospheric transmissions. His rich sonic explorations of and between electronic and acoustic tone were characterised by a treatment of acoustic instruments that focused on sonic phenomena, rather than established notions of musical gesture. Working closely with engineer Tom Hamilton in the realisation of electronics in his works, Lucier focused on combining close tunings with the control of these different sonic phenomena, showing listeners how human interventions with sound will always lead to music. Importantly, these explorations were grounded in performance – in the ephemeral possibilities of liveness and interpretation. He often engaged new technologies in his performance installations, such as the echolocation devices used in ‘Vespers’ (1968) and an electroencephalogram (EEG) machine in ‘Music For Solo Performer’ (1965).

‘I am Sitting in a Room’ (1969) is probably one of his most well known works, a performance for recording piece that explores the relationship between resonant frequencies and recording technologies, where Lucier seeks to turn speech into music. In this work, the narrator records themselves reading a text, playing it back into the room, repeatedly re-recording it until the resonant tone of the room comes to the fore and speech simply becomes sound. Lucier’s own recordings and performances of this piece almost feel like the only version of this work, perhaps due to his personal connection to the spoken text. But whilst I personally relished the conceptual reward of having the composer speak, the work is scored for any performer. Lucier was of a generation of electronic music peers committed to notating music, perhaps in part reflecting his classical music training, but also his interest in having electronics performed. He adopted a wide range of notational approaches that would enable the sharing of his works, involving text, drawings and traditional notations for a wide variety of sound sources, that ensure the ongoing engagement with the performance of this works into the future.

My first involvement with Lucier’s work was in a telematic performance of ‘Quasimodo The Great Lover (1970) for one or more microphone -amplifier – loudspeaker systems, a performance work inspired by the long distance communication systems of whales, and organised by Matt Rogalsky and Laura Cameron in 2007. Approaching his eightieth birthday in 2010, my new music ensemble Decibel, a group committed to music where electronic and acoustic instruments combine, presented an extensive retrospective of his work in Perth, excerpts of which later travelled to regional WA and nationally. Many of these works were heard in Australia for the first time, and recorded as part of a monograph release on US label Pogus. The list of works is representative sample of the sheer range of approaches Lucier employed for his explorations of sound: ‘Shelter’ (1967) for vibration pickups, amplification system and enclosed space; ‘Ever Present’ (2002) for flute, piano, alto saxophone and sine tones; ‘Hands’(1994) for organ with one or more players; ‘In Memoriam Stuart Marshall’ (1993) for bass clarinet and pure wave oscillator; ‘Nothing is Real (Strawberry Fields Forever)’(1990) for piano, amplified teapot, tape recorder and miniature sound system; ‘Music for Snare Drum, Pure Wave Oscillator, and One or More Reflective Surfaces’ (1990); ‘Carbon Copies’ (1989) for saxophone, piano, percussion and environmental recordings; ‘Directions of Sounds from the Bridge’ (1978), a sound installation for stringed instrument, audio oscillator and sound-sensitive lights, as well as selection from the ‘Still and Moving Lines of Silence in Families of Hyperbolas’ (1973-1974) collection of works for acoustic instruments and pure wave oscillators. The concert also featured a performance of ‘I am Sitting in a Room’ (1970), featuring well known local newsreader, Peter Holland. His music had an overwhelming influence on my own, it taught me to slow down and listen, and that there is still a place for scores in the performance of electronic music.

Many other Australians have engaged with his work, some examples being clarinettist Anthony Burr’s performances and recordings, Oren Ambarchi teaming with US guitarist Stephen O’Malley to commission ‘Criss Cross’ (2013) for two guitars, and the Australian Art Orchestra commissioning of ‘Swing Bridge’ (2017) for organ and ensemble, premiering at the Melbourne Town Hall. When US academic Douglas Kahn moved to Australia he shared a wide range of perspectives on Lucier’s work in his writing and presentations, and electronic music artists such as Peter Blamey undertook research into Lucier’s work. And there were a range of earlier performances of Lucier’s work in Australia, some of which confused critics, with one article headlining a 1984 concert at ANY as ‘High Tech Aural Sadism’ in the Canberra Times.

Swing Bridge by Alvin Lucier. Premiere performance by Australian Art Orchestra from Australian Art Orchestra on Vimeo.

Lucier was a long-time music professor at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, a generous teacher and inspiration to many explorative minds, including his student Daniel Wolf, whose German based Material Press publishes Lucier’s scores. These include works for multiple electronic instruments, such as ‘Gentle Fire’ (1971) for any number of synthesisers and ‘The Duke of York’ (1971) for voices and synthesisers – works that emphasise the collaborative possibilities of electronic music performance. The books ‘Music 109 – Notes on Experimental Music’ (2012) and the lectures he had invited over his many years of teaching in his edited collection ‘Eight Lectures on Experimental Music’(2017) are wonderful documents of his teaching approach, and offer a range of insights into his and his collaborators works.

I was fortunate to cross paths with Alvin Lucier on a few occasions, and remember him as a warm, generous man with a great sense of humour. We first met in Middletown, when I was shortlisted for the teaching position, he retired from in 2011. It was like walking into a living text book of American experimental music– meeting Anthony Braxton, Christian Wolff and Ron Kuivila, having dinner at the Lucier’s with Robert Ashley and Mimi Johnston. I didn’t get that job, but Lucier and I spending an evening ranking various Italian operas and arias over Thai food in a local Middletown restaurant is something I will remember forever. He was a fantastic cook, and his recipes often appear in his interviews and books; I still use his soba noodle recipe I found in one of his books. After keeping in touch online, we met again at Tectonics Iceland in 2014, which was to be the was the last time I saw him in person.

The news of his death arrived when I was on Mount Hotham, Victoria as part of the AAO Creative Music Intensive. Jasmin Wing-Yin Leung, Nick Ashwood and I paid homage to him by placing a computer playing a recording of Decibel performing ‘Ever Present’ as part of a soundwalk. The sounds drifted over the mountainside amongst the trees, I think he would approve. Alvin Lucier inspired, performed and wrote music that challenges our conception of both sound and music, helping us to listen differently and appreciate the richness of the sonic world we live in. He showed us the ways we can perform with and in with electronic sounds and processes. Engaging with his music informed my own practice in so many ways, and I am in debt to him for my conceptual and performative approaches to composition with electronic sounds. He leaves an important and poetic legacy for us all in an ongoing interrogation of sound of all kinds, that will be performed and enjoyed in the years to come

Cat Hope is an Australian composer, performer and academic living in Melbourne.