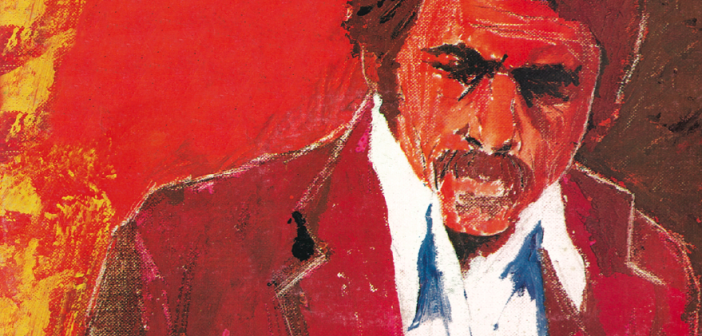

Broken men, broken homes and broken towns – the landscape Lee Conway presented at the turn of the tumultuous 1960s spoke of ruptured traditions and dislocated people. Through paeans to hard-luck working families, hobo drifter laments or tales of urban alienation, Conway celebrated and investigated the downtrodden, dispossessed and dispersed. He sang a unique, externalised and masculine melancholia. The song of the lost, those severed from their roots and lore, melded in the fragile crucible of suburbia.

Personified through the infirm and untethered – crippled children and heartbroken eccentrics – the 1970 Australian male often saw the world from the outside looking in, projecting inner torments and displaced compassion onto external totems and cyphers (whereas the contemporary male can only investigate cyclical internal terrain). In a rich early catalogue (whether self-penned or by regular muses Doug Ashdown and Jimmy Stewart), Lee’s uncommon studies in manhood offer a singular vision that anticipates abandonment and an event horizon of fractured gender roles.

That Conway – the artist – should paint a turbulent sonic tableau would come as no great surprise: he was delivered to these antipodean shores through crisis, at a time of seismic social and cultural upheavals.

Born March 10th 1944 in war-torn Poland, Lee’s family emigrated to Australia when he was three. They settled in Fitzroy, one of Melbourne’s oldest suburbs, as part of a large post-war influx of european migrants that displaced the area’s traditional working-class inhabitants. Early 1950s Fitzroy was a rough place, regarded at the time as a slum, the state government cleared large tracts of housing to erect pristine and soulless towering commission apartment blocks. The young Lee had fallen in with a disreputable crowd, and his fearful parents decided to move south of the Yarra river (far enough away that Lee couldn’t ride his bike back to Fitzroy).

Now resident in Aspendale, Lee had his first real exposure to music, milling around the local milk-bar on Sunday afternoons and breathing in Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley. Soon Conway discovered the Mordialloc Life Saving Club, a wildly popular local dance venue and home to rockers Bobby Cookson And The Premiers. Accordionist Stan Azzopardi taught Lee the tub bass and he joined the group for a brief time. It was also then that Lee first heard Johnny Cash, an elemental simplicity and sound that struck Conway deeply.

As one of The Premiers, Lee played to thousands of delirious kids at the Malvern and Springvale Town Hall gigs. Conway soon left the band though, and by 1967 was managing The Laurie Allen Revue, with a busy concert, television and recording schedule. But he tired of the showbiz grind, and decided to get into…the trucking business.

Lee bought a truck and started to ship freight, on long-hauls and overnighters, on dusty desert highways and parched interstate blacktop. Burning asphalt in his rig, Lee heard a striking new voice over the radio – Lee Hazlewood. The moustachioed maverick’s duets with Nancy Sinatra (‘Sand’ and ‘Jackson’) entranced Conway’s ear, and on a layover in Adelaide Conway eagerly snapped up a cassette tape of the pair.

Lee soon found himself spending more time in Adelaide and sharing a house with Colleen Hewitt and Doug Ashdown. The house was next door to Gamba Studios, established by Le Mans racing driver and Penfold’s Wine heir Derek Jolly. Jolly was a progressive, colourful character and had an open door policy, inviting musicians to experiment in his state-of-the-art studio. He also invested in a Futuro House, installed the first Moog Synthesiser Mark III outside of the U.S.A. and collaborated with Dutch ‘musique-concrete’ maestro Henk Badings.

It was in this studio that Conway cut his first demos (one of them – John D. Loudermilk’s ‘Half Breed’ – is released on Lee Conway: I Just Didn’t Hear (The Early Roads 1969-1973) for the very first time) and then progressed to record his first 45 (produced by Jimmy Stewart), the May 1969 issued ‘Fine White Stallion/Forty Coats’.

The gentle folksy jazz of ‘Fine White Stallion’ implores the listener to depart on a whimsical and etheric escapade, while ‘Forty Coats’ charmingly describes an eccentric naturist and drifter who left society behind when his beloved left him heartbroken.

A few months later Lee cut his next single, the rugged and romantic roaming testosterone fantasy ‘Wanted Man’ and it was issued in early 1970. Conway had copped the song from Bob Dylan (via Johnny Cash’s ‘At San Quentin’ LP). Poet, recording artist and future ‘shock-jock’ John Laws featured Lee’s 45 on heavy daytime rotation and it became a chart hit. Lee Conway was on his way.

A flurry of activity followed – 1970 saw two more 45s released (in May and December respectively): ‘Jody And The Kid/The Other Man’ and ‘Something New/Love And Little Joe’, all on the Adelaide based Sweet Peach label. Conway made numerous live and television appearances to promote the releases – performing in Melbourne, Sydney, Darwin, Townsville, Hobart and other centres (and on the small screen amid appropriately atmospheric sets on ‘Hit Scene’ and ‘Happening ’71’).

Lee’s first LP also hit the shelves around this time – ‘Adultery’ – a combination of duets (with Ann Irwin), originals and judicious covers. ‘You’d Better Sit Down Kids’ was a reflective and mournful divorce lament, while ‘Lovers Such as I’ came across as a mildly trippy outtake from a Dean Martin/Lee Hazlewood love child.

By now the schedule had become relentless and 1971 saw the release of the titular 45 ‘I Just Didn’t Hear’, a masterpiece of masculine introspection and self-examination. Along with studio musicians Doug Ashdown, Kevin Johnson (and producer Jimmy Stewart), Conway crafted the perfect distillation of mood, pedal steel riffage and anthemic embittered regret. Conway’s television performance of ‘I Just Didn’t Hear’ on ‘Happening ’71’ reached the very heights of roughhewn Antipodean Gothic Noir.

Soon after, the ambitious quasi-conceptual country LP ‘Applewood Memoirs’ was released (on Sweet Peach domestically and Ember in the U.K). Home to grand swamp narratives like ‘Love And Little Joe’, windswept epics of failed urban affluence such as ‘Mothers And Sons’ and the barren ejected material aspirants of ‘The House That Love Built’, the album was a triumph of poetry, performance and keen-eyed arrangement. Lee as a burly outback Bobbie Gentry, painting timeless, intimate arcs and vivid narratives.

Conway toured locally with, and befriended, Jerry Lee Lewis (who later took Lee on a house visit to Elvis) and did an extensive set of dates in the U.K. with Slim Whitman in October 1971 (where he was billed as ‘Australia’s Number One Country Singer!’), playing headline shows at Wembley and the London Palladium.

On an extended stint in the U.S. (drumming up interest and T.V. appearances) Lee wrote the bulk of his next album, ‘The Stories We Could Tell’. Another epic song-cycle of melancholic, finessed arrangements, alienated wanderers and hard-scrabble unfortunates – the LP was recorded at A.T.A. Studios in Sydney and produced by Denis Whitburn. It was recognised by the Australian Federation of Broadcasters as album of the year. Opening track ‘Coalmine’ bounces from stringed jig to coal-dusty lament, as the smooth gloom of ‘Lonely Life To Live’ and the cavernous ‘While The City Sleeps’ are radiant highlights.

As the 1970s blossomed, every door opened for Lee, his singles charted in the U.S, he performed for the Queen and landed his own prime-time T.V. show at home nationally on Channel 9 (‘Conway Country’) that ran for years. The former real-life trucker, cut trucker albums and country-pop crossover hits.

On Lee Conway: I Just Didn’t Hear (The Early Roads 1969-1973) you get to hear those affecting early sides – perhaps eclipsed in the popular consciousness by later years of glitter and glitz – yet vital, disarmingly assured and singularly poetic.

As of this writing, Lee Conway is putting the finishing touches to a brand new, and apparently strikingly good, recording.

So welcome to Conway country – a place where the yearning male spirit grapples deeply with tectonic changes in the emotional landscape and shifting cultural vistas. A place where an earthy baritone and an eye for insightful observation, just might help you make it to the morn.

Lee Conway: I Just Didn’t Hear (The Early Roads 1969-1973) is out on Omni and available from here.