The felling of Tasmanian old growth forests has for many years been an issue of serious concern for Tasmanians and Australians alike. Allegations abound that logging companies have long ignored the need for a sustainable logging culture, logging illegally and, depending where you stand on the issue, immorally for decades. But regardless of the legality and/or morality of these activities the result is the same – the eradication of hundreds of thousands of hectares of old growth forest, the irreplaceable loss of an ancient natural wonder.

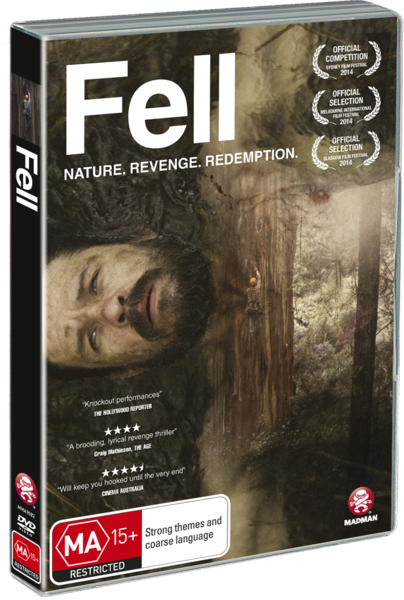

Which brings us to Fell, the debut Australian feature by Kasimir Burgess, a film exclusively, uncomfortably, unflinchingly about loss set in the midst of a land defined by loss. We meet Thomas (Matt Nable) and his daughter, on a camping trip deep inside logging country when, with little warning, the young girl is mown down by a truck loaded with toppled trees on a rain-soaked road far from help. The Driver, Luke (Daniel Henshall), panics, drops the clutch and races from the scene of the crime. The hitting here is an accident; the crime is in the running. It’s a jarring, even unpleasant, way for the film to begin and of course it needs to be, as it’s a moment that will inform the lives of these two men for many years to come.

What follows this tragic intersection of two lives is a mediative and predominantly quiet examination of how they struggle to deal with the grief and the guilt, while their trajectories are inevitably drawn back together. Thomas unquestionably carries the heavier burden, and much of the film’s tension is drawn from the question as to whether he will escape from the desperate, potentially vengeful, spiral he is caught in or succumb to it. And it’s here that Matt Nable as Thomas performs an admirable job in a difficult role. Whether brooding, glowering or running naked through the woods, he communicates a lot with a little, fully demonstrating the tinderbox physicality of a man set to combust. While Daniel Henshall is invaluable in the role of Luke, a man, not faultless by any means, struggling to bear the guilt of what he has done while trying to move ahead in the world, proactively, for his own sake and that of his daughter (conceived, perhaps a little too neatly, in a grimy fit of passion following the accident). He brings a lightness of touch that helps to inject some much-needed levity whenever he’s onscreen, without ever allowing us to forget the gravity of his own situation.

But if you came for the grief, you should stay for the forests. It’s the natural world, the destruction of which provides these men a living, that steals the show. Marden Dean does a wonderful job of capturing the might and majesty of these sacred places and his images of stunning visual poetry assist greatly with the wistful, lyrical mood which permeates the entire film. Make no mistake, these trees are stoic and strong, mighty and wise, they dwarf these men and their problems, and we cut them down. I can’t quite tell if Burgess intended to employ the story of these two men purely as a metaphor in order to eulogize these disappearing old growth forests, but I hope so.

For while the film certainly looks beautiful, and is more than competently produced, there are times you might stop to wonder in service of what. As a pure examination of grief and resilience the film succeeds. The ‘where’ and the ‘what’ are clear, a workable tagline might be “A man struggles with grief in the woods.” But those looking for an answer as to ‘why’ may be dissatisfied. Why does Thomas arrive at the decisions he arrives at and why, when the admittedly tense climax does arrive, does he make the choices he makes? He spends so much of the film like a coiled snake, mute and expressionless, that there can be no question he’s a man being eaten alive by grief, but what else? It could be that in insulating himself from the horrors of the world, Thomas may have gone too far and left out the audience as well.