I was actually mildly surprised when I received my review copy of the newly re-released Flesh to learn that, in fact, Andy Warhol didn’t have much to do with it. Just like the Velvet Underground, who Warhol ‘managed’ and ‘produced’, the film really has a history of promotion via a Warhol connection (indeed, the film has long been known by the alternative title, Andy Warhol’s ‘Flesh’), rather than any real, direct involvement. He is, officially, the producer. Paul Morrissey, Warhol’s friend and sometimes collaborator is, of course, the actual director of the film. And, while the actors involved are all known as member of Warhol’s Factory, Morrissey himself has often complained that they all came to the Factory having been discovered by himself, the Warhol ‘superstar’ being subsequently added to their mystique. Which is all a very roundabout way of coming to the point that, ultimately, Flesh is a supremely Warholian work and bears many of his signature traits.

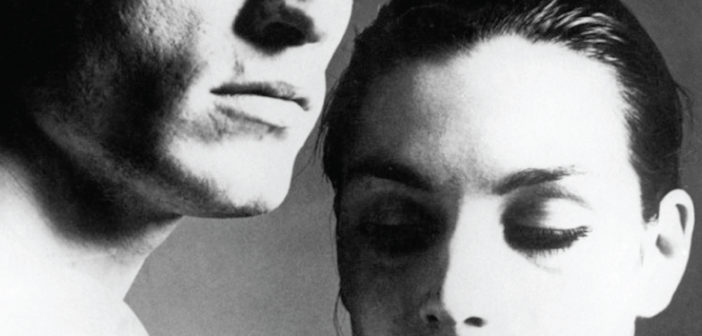

Two scenes, indeed, are pilfered directly from earlier Warhol films. The opening sequence, a minimal depiction of a sleeping Joe Dallesandro, is a direct lift from Warhol’s first ever film, 1963’s Sleep. Here, however, the homo-eroticism that was carefully tiptoed around in Sleep is made more explicit with the overlay of ‘Making Wiki-Waki Down In Waikiki’, from the 1930s, as the soundtrack. Later, Warhol’s Blow Job film from 1965 is homaged in a scene where Joe is turning one of his income earning tricks. We see the act of him being fellated but, as with Warhol’s earlier b&w film, nothing below the actor’s head is shown on screen.

As well as direct Warhol references, there is also the structural features of the film. Low grade ‘acting’, editing cuts which feature a flash of white for each visual edit and a loud clicking noise whenever footage that includes live audio is used, and a general lack of traditional plot are all devices actively explored in Warhol’s own films. This breaking down of established film-making technique is certainly not something instigated solely by Warhol, but the blurred edges between formalist experimentation and plot driven entertainment is something that Morrissey is certainly developing here. It is, however, the formalist qualities which are most successful. The best scene in the film is a silent one, showing Dallesandro playing with his real life, one year old son. It’s both emotionally tender and formally beautiful, devoid of any real connection to what little plot does run through the movie.

Ultimately, you can’t really watch this movie and attempt to enjoy it as escapist entertainment. The plot is wafer thin (basically involving Dallesandro’s wife telling him to stop being lazy, go out and earn some money pulling tricks so that she can pay for an abortion for her friend, and then Dallesandro doing that) and the ‘acting’ is horrible, not even approaching untrained naturalism but wallowing in horrid (often drug induced) affectation. There are other disturbing elements that arise from the actors attempting to just play out what they experience in their everyday lives, as well. For example, one scene where Geri Miller’s character, Terry, (with Miller herself looking rather stoned) describes some details of a rape she had experienced. A minute later she states that it was bad at the time but, thinking back on it now, it was kind of fun. Whether this is a sign of the attitudes of the (free love) times or a deliberate attempt to shock, it’s still an attitude that’s incredibly disturbing and difficult to excuse.

In the end, the title is probably the best filter through which to view the movie. Flesh works best seen as an ode to Joe Dallesandro. Contrasting the traditional western mode of objectifying the female, Flesh really is an objectification of Dallesandro. And it can’t be denied that he is extremely beautiful, whatever the context. Like Warhol’s Screen Tests film portraits of anybody who happened to drop by the Factory, the fact that the camera remains unflinchingly attached to Dallesandro’s face and body has interesting results on the way we view him as a human. In the film, he is objectified by his wife, by his wife’s friend, by the artist who pays him to model for him, by the drag queens who don’t really notice his presence. Layered on this, the camera well and truly objectifies him which, in turn, means that we as an audience do likewise. Which in itself becomes a very interesting and loaded tactic. The second wave of feminism, heading towards being in full swing by 1968 when the film was made, actively sought to desexualise the male gaze in western culture. In this, it ultimately failed. What has happened, therefore, is that post-modern waves of feminism have been more interested in sexualising the female gaze in order to level the playing field. Morrissey was notoriously asexual in his dealings with folk around the Factory and this informs much of the ambiguous sexual politics of the film. Females are not generally objectified while males are. Dallesandro, in particular, is obectified by both males and females. So the female gaze is sexualised. However the sexuality of the male gaze is simultaneously widened into the, until then, usually hidden away, homoerotic. Whether this widening of the sexualisation of the male gaze is feminist or counter-feminist is something I’m still not certain about (though I have my doubts).

Flesh is not entertainment. Well, I didn’t find it entertaining, anyway. However, it is thought provoking and I’ve spent a whole lot more time thinking through its implications than I would for the average ‘entertainment’s film. I do find it interesting that Warhol’s 2 and 3-dimensional art, the stuff he declared was dead when he began making films in 1962, has aged considerably better than his film productions (as opposed to the films he actually directed, which share much more, æsthetically, with his still works). Flesh is very much of its time. Indeed, if it had more in the way of content it would probably act as a period piece. It struggles to bridge the gap between formalist art and Hollywood derived narrative, while still prodding a large number of its own unique questions.

And then, there’s the final scene. Joe’s wife has invited her pregnant friend over. They lay about on a dishevelled matress on the floor that serves as a bed, Joe naked, the women clothed. The women admire Joe and discuss further banalities. Some affected interaction between the women hints at eroticism, but then they all decide they’re bored and fall asleep. The film ends.

Adrian Elmer