In their time, and up until the last couple of years, The Flying Lizards were mostly thought of as a joke band. Australian artists have been among the first of a new generation of musicians to appreciate and benefit from what The Flying Lizards were doing. You can hear their smart pop gently filtering through the sounds of Fabulous Diamonds, Absolute Boys and Naked On the Vague (Matthew Hopkins of NOTV speaks later on about the impact of The Flying Lizards on his music).

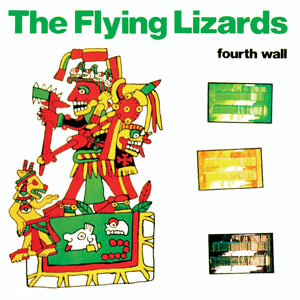

Everyone knows The Flying Lizards’ hit cover of Barrett Strong’ “Money’, from their debut self-titled album (which also sold pretty well), but this article brings to light their incredible, largely unnoticed second album, Fourth Wall, which collided many of the best avant composers of the 70s and 80s – Michael Nyman, Steve Beresford, Patti Palladin, Robert Fripp, Peter Gordon, etc and the man who is The Flying Lizards, David Cunningham – to make a pop album.

1981′ Fourth Wall really proves how great a producer David Cunningham had become. He samples everything from the flute music of New Guinea to audio from a Hitchcock documentary, adds some colouring from some special music friends, then swirls these layers of abstract sounds into some very romantic grooves; years ahead of those days.

I visited David Cunningham 30 years later at his London pad to talk about the album. Piles of paper, records, and machines as tall as people fill each room of the apartment (including the bathroom) with comfortable pathways to all the household necessities. He sits me down at his small circular dining table with a cup of tea and begins the story of Fourth Wall.

David Cunningham: It took the best part of a year and then a bit. “Cause I had sort of finished it and Virgin were saying “Get a move on, get a move on.†Then I finished it, and they said “Oh well it’s not very good, go and do a bit more.†There was also sort of a phase of … we had a version of the record and we went and tried it out live. Just as a one-off thing with this really weird collection of people. Most of Michael Nyman’ band on one side of the stage; that was the strings and brass and bits and bobs, and Nyman on piano. Then on the other side of the stage was the rock bit. J.J. Johnson of The Electric Chairs on drums, Georgie Born out of Henry Cow on bass and um, I can’ really remember what else.

Samuel Miers: Did Patti sing as well?

And Patti Palladin singing, yeah. We rehearsed separately which is kind of odd. Basically, with rock musicians and orchestral musicians, you have to work with them differently. You have to get the orchestral ones playing the parts sort of right, and the rock ones have to work with a vaguely improvised structure, or else working around the chords of the song. Of course, if you’ve got J.J. thrashing away on the drum kit and you’ve got orchestral instruments there in a rehearsal setting, you can’ hear a thing. The day of the gig was actually, I think, the first time we put the two together. It was very mixed, what came out of it. There is a tape but nobody’ heard it except for me and Patti. It was only recorded on a 4-track though, that 4-track (David points to the other side of the table and laughs).

So how did you come across Patti Palladin? Was it through Snatch?

I was a big Snatch fan. To me they were kind of like in the tradition of The Ronnettes and The Crystals and stuff like that, and that was music I really loved since I was a kid. They were pre-punk as well, you know. The first Snatch single might have been in 1973, I think, I’m not sure. I was very aware of them being around, [but]I had no idea that they were kind of like real people that you could talk to or meet, or anything. I worked with Jane County/Wayne County in 1979 producing her last album as Wayne, before she became Jane. She knew Patti, she asked Patti to come in and do backing vocals with her. I met Patti, obviously, I was producing, and we got on very well and I enjoyed working with her. She liked what I was doing, because if you know Wayne County’ work before that, you know it was very kind of straight line punk stuff. I took it in a slightly different direction, maybe two slightly different directions, at the same time. Patti could hear what was going on and she thought this was interesting and we have had an ongoing dialogue after that, I guess.

Matthew Hopkins of Naked On the Vague on Fourth Wall

Since I began making music, The Flying Lizards have always been on my brain as a major influence. Their music really made me think about how strange pop music could become. The Fourth Wall album is one of my all-time favourite records. There are some really weird noises and incredible ambient moments on this album. This has probably been the most influential element of their sound – the use of loops and tapes and bits of noise amongst a basic pop song structure. The use of guitars on this album was particularly ear-opening for me. I grew up listening to metal and crappy punk and mostly guitar music. I thought the guitar was essential if I wanted to start a band. But when I heard stuff like Flying Lizards I saw that guitars did not need to be the “thing’. The guitars on Fourth Wall use simple interesting effects – they blend with the tapes, synths, brass etc., and don’ stand out in stark contrast or anything – and there are some mean solos going on! When I first started making music, I was incredibly worried that you needed to be able to write everything on guitars. The Flying Lizards taught me a valuable lesson otherwise.

“Lovers and Other Strangers’ is one of my favourite songs; it sounds like it could be the theme song to a Surrealist sitcom or something. “An Age’ is also a highlight; it’s such a futuristic sounding piece, such a great “riff’. The track “Cirrus’ and the other ambient moments on the album make the perfect break between the songs. Since hearing Fourth Wall, I’ve always made a conscious effort to include short intros, or ambient breaks in between longer, more structured songs on my own recordings. I feel this strategy makes more of an album, more of a whole. These pieces act like small pauses for relaxing and gathering your ears and brain.

You produced some things for her after Fourth Wall as well didn’ you?

Kind of. It’s more co-producing, I guess, basically just decorating. She pretty much looks after her stuff. She’ a superb producer. There aren’ very many records under her name. Copy Cats with Johnny Thunders, that’s Patti as a producer, but not in name, because Johnny wouldn’ let her. His chauvinism is too much to be produced by a woman.

What about Michael Nyman, what was he like to work with?

I can’ remember if it was when he formed his band, but “round about maybe 1974, I came across him performing in art galleries. I used to write for a magazine called Musics. Musics mostly dealt with improvised music and a bit of the composed avant-garde. People like John White, Michael and Gavin Bryars and so on. While I was a student – I was an art student from 1973 to 1977 – you had to kind of produce something written every term, and I basically just went and reviewed these gigs and wrote those up as kind of little comment, essay, critical essay things. I also published them in Musics, simply because I sort of felt it was important in that context of improvised music to make a reference to composed music as well, because they traditionally sort of hated each other. While there was a vibe building up, partly because a lot of the composers like Cornelius Cardew and Gavin Bryars decided that improvisation was a dead end and they weren’ going to do that anymore, whereas they had been quite involved before. There was a bit of factionalism going on, and I just thought “let’s mix it all up again’, “cause I like both.

So I was reviewing Michael’ gigs, releases etc. One of his bands with five grand pianos put out a cassette, and I reviewed it and I gave it a really sort of … I said it was rubbish, really. I said it very eloquently in terms of the way experimental music was working. I said, you know, it’s got all the things that experimental music has; it’s recycling old tunes, it uses repetition, it’s got multiple instruments – multiples of the same instrument – it’s got a lot of those key elements that a lot of experimental music had, but yet it’s awful. So I wrote this review; musicologically, a very sound review. We had Gavin Bryars teaching us at our art school at Maidstone in Kent. Gavin actually decided to give up teaching us, so I came in on a Tuesday morning or something. The issue of Musics had apparently hit the streets in London but I hadn’ got my copy out in the sticks in Maidstone, and there was Michael Nyman sitting on the table, swinging his legs, reading a really bad review of himself. He appreciated the fact that I’d actually done the work to kind of say why it was rubbish, this particular piece of music. We sort of developed a kind of conversation out of that, which basically continues to this day. After I’d done a few bits and bobs with a few other people in the late 70s, Michael asked me to come and help him mix some stuff he’d done for a Peter Greenaway film called The Falls. I’d heard the band he put together playing this stuff and I liked it, so basically we ended up doing an album.

So how was the collaboration process working in the studio, with all these contrasting music brains?

So I’d record a bunch of stuff with different people, loads and loads of just backing tracks and bits. Kind of just guiding them into: “try this, play this, play along with that’, and then I’d take those tapes, mix them, and then chop them up and repeat bits, and re-edit and so on. I didn’ know at the time, but that’s how David Bowie worked as well, except he was using two 24 tracks. He’d get the band sort of playing something, if he got a verse that he liked, he’d just copy the verse and edit all the verses together or something that would become a verse subsequently. It’s a way of basically constructing stuff without actually having to write the song in advance, if you see what I mean.

“Glide/Spin’ smooshes together as probably my favourite track on the album. The vocals are so sad. How’d this one happen?

I was putting together the song shapes for “Glide/Spin’ without Patti, and she’d kind of listen to what I’d done and say “Oh this fits with this song that I’ve got,†you know, rhythmically, lyrically or whatever. So there was a song that she had called “Spin the Bottle’, and a backing track that I had fitted her words to. So the two kind of get superimposed. I had a backing track, started off with a drum machine, added some kind of strange tabla thing. There are two mouth organs; oh, this is a good one. It’s two tape loops of mouth organ playing and they’re just cycling out of time.

Why do you think that Fourth Wall didn’ do as well commercially as the self-titled?

Because Virgin hated it and they wouldn’ promote it. Also “cause the general expectation was that The Flying Lizards made cover versions of R & B classics.