WOMAD is some sort of pulsing snowball of musical fertility erupting on the barren plain of the musical year. Where else can you see cumbia back to back with a Syrian wedding singer? And be served a wind of Ukrainian snowlands delivered on the breath of the girls of Dahka Brakha? Their harmonies, so richly interweaving and at times deeply deeply sad are seldom heard in this country! Swimming in cello thick and dark as molasses, modern composition drawing on persistent, strident tradition, surprising when modest Marko Halanevych adds his voice, and dropping into abyssal darkness as the bow skittered down the cello’s strings brittle as falling ice. Did they say, this is a song about our land, we must protect it, or did I only imagine it, to see their voices raised before the goliath pines of the gardens? Few groups have such sonic and visual appeal, are able to take the crowd from dirge to dancing. True standing ovations were the result; their cds sold out.

Ukraine modern prog-folk ensemble Dahka Brakha. The band’s name means ‘give and take’. Photo by Amy Bayer.

‘Shall I eat this, or shall my daughter, or my granddaughter, eat tonite? And they would choose suicide.’ These were the words of Tania Tagaq, inuk throat singer, in describing her land. Scapes of flat ice without vegetation, nights nearly infinite. Tagaq taught herself her craft from casette tapes sent to her from her mother… allowing her, evidently, to take what was traditionally an art and game between two women, face to face, inhaling each other’s circular breathing, and carry it to realms of experimentia and electronica. Not casual listening! From growling, grunting basal sounds with Tagaq writhing low on stage to fairyesque sweets floating high on chilly breezes, Tagaq performs something intensely unique: during her first show, half the crowd left, and the rest, were utterly transfixed. Some of us were in love yet terrified. When asked about collaboration with an Australian artist, Tagaq responded that to do so she’d need to connect with our land. Go out into the bush, she said. See some animals, maybe kill one and eat it.

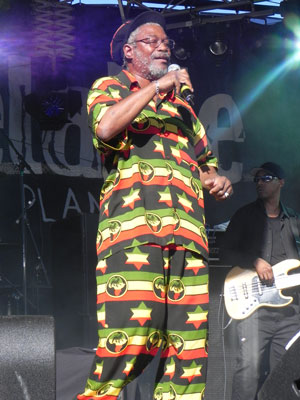

Jamaican reggae legend Horace Andy shows his colours. Photo by Amy Bayer.

One thing astonishing about the festival is its ability to deliver true legends. I in my infinite cynicism put no faith in the quality of Horace Andy’s prospective performance, despite the fact that his 1983 album Dance Hall Style is an undisputed seminal reggae classic and a treasure of my musical hoard. Not despite, but because. So many great artists have belated comebacks, flaring brief as meteors and gathering as much cash as possible in a disappointing last crash to earth. !Gloriously! wrong I was. Here was the real man skanking up a real jamaican reggae party, moving with his (super-tight) band, moving with the crowd, tunes rolled back – tunes galvanised with brass, descending into dubby dreams. Only true legends can make a song sound fresh and yet retain the sense of familiarity, and play a rythym thirty years old with new style and unforced zest. Thankyou Mr Andy.

To be blasphemous WOMAD is the messiah of multi-artist gigs. There’s too many moments, its not easy to absorb. Hidden delights aplenty. N’Faly Kouyate, kora player of Afro Celt Sound System, received no separate billing on the program, and in a way that’s good, for some things to be reserved for those who seek with greater perception. For the first time, N’Faly presented an audience with his tribute to his late brother. Amadou and Mariam, blind songwriters from Mali, are the kind of performers that no one can resist. They are having too much of a good time, looking too irresistably happy. After all, if we were drawing on an aural wealth spanning the Sahara itself, wouldn’t we all be, at the least, happier?

Passing the ‘taste the world’ tent at some indetirminate time, I came across the start of chicken being prepared by Rango, Eygyptian based band incorporating Sudanese music traditions and taking their name from the almost-extinct xylophone of which Hassan Bergamon is the last known player. These guys are not young ducks themselves, but they make their music in order to interact with revered spiritual entities and heal people who come to them with cases of grief, depression, or sickness. Its incredible to see them dance, to take up shakers made from used insectspray cannisters and make people move. For this particular occasion they first put on the rice. Whilst it was cooking, it was time for a song. With only 50 or so seats, the food tent is WOMAD’s most intimate stage. Then the chicken. Normally, one of the band members kills the chook, but in this case, courtesy of the supermarket, we heard a song from the chook-killer instead. More dancing, and another round of contagious melodies from Africa. Text on the cover of their album Bride of the Zar declaims No chickens were harmed in the making of this album. Secret spices added next, then time for another song as we wait for the bird to cook. By the time we got to try the food, it was the last in a line of vivid flavours, and we were healed whether we thought we needed it or not.

Malian singer-songwriters Amadou and Mariam. Photo by Amy Bayer.

Its nice to see an audience bamboozled. Peformance conventions too much are ingrained and invisible. Watching dance and song group Huri Duna of Papua New Guinea move amongst the edge of the crowd as another act performed, replete with bird-of-paradise head-dresses, yellow and black face paint and lappets of fresh foliage, opening cans of drink and posing with families, it was tempting to wonder whether this in itself was a performance, a way of increasing the lushness of the festival atmosphere. Curiously a small audience awaited their scheduled show, and were so unprepared for the men to surge out from beside the stage, clearing seated spectators from their way with knocked arrows pointed at faces; the audience, in response, ran to meet them, only to find they were not so sure they wanted to be so close as the dancers moved in formation, skirting the stagefront, curling around the edge of the crowd, reforming in inward-facing formation, their faces transformed by colours and adornment, as if a parliament of old gods. Just when people thought it safe to approach, they moved again, passing like a pod of two legged rhinos, their footfalls soft and heavy on the earth spongey with the years of leaf-fall from the exulted trees above. Some mistake natural for unrefined. But everyone has seen images of the immense gatherings in highland New Guinea. These people have been working crowds for way way longer than us! They know the way the inimitable intricacy of feather forms draws the eye, the way watchers might almost forget their presence as they close ranks in circle and call forth a little song of almost delicate almost innocent beauty, then those daydreaming spectators suddenly find themselves passed closeby by armed men not one of whom weigh less than 90 kilos. The whole arena was Huri Duna’s stage, the trees their pillars of righteousness and the audience, astonished, puzzled, and some so foolishly happily none the wiser.

Fun during dinner with Rango, faith healers from Egypt. Photo by Amy Bayer.

WOMAD delivers, and cannot be compared from one year to another in terms of artistic quality or abundance. As ever it is cunningly administered, its diversity nurtured and resown, and commercialism restrained. Great thanks to those with the love and forsight to plant the living deities in Adelaide Botanic Gardens and to those who tend them and prepare the area so well. Next year is coming, and that is salvation.

Lindley McKay