Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the Clan Analogue collective grew from its early beginnings in a Sydney apartment into Australia’s largest independent electronic artist network, as well as a significant record label in its own right, with around ten albums and eight compilations in its back catalogue to date.

At a time when local live electronic performers were still struggling to find switched-on venues, Clan Analogue provided an alternative to isolationist studio noodling, as well as a forum to exchange ideas, techniques and opinions that was previously missing amongst the then rock-dominated entertainment landscape. What started with a group of like-minded studio subversives in 1992 soon became a thriving, ever-growing nationwide collective by the end of that decade, with chapters in almost all major Australian capital cities and several Clan-affiliated acts such as B(if)tek, Disco Stu and Deepchild all enjoying considerable airplay on Triple J and RAGE. While new releases from the Clan Analogue label have been relatively sparse over the last few years, the arrival of Clan’s long-promised ‘Re: Cognition’ 2CD /DVD retrospective set sees the gears whirring back into action, as well as providing a fittingly extensive document of the collective’s history to date. As well as two CDs respectively featuring a selection of classic Clan tracks and a collection of new remixes, ‘Re: Cognition’s accompanying DVD presents a previously unseen documentary, the majority of the collective’s videos to date and early footage recovered from the long-deleted ‘Live At The Goethe Institut’s VHS.

When approaching a history of the Clan Analogue collective, one of the first obvious ports of call is founder Brendan Palmer, responsible for conceiving the collective back in Sydney in 1992 with a few other people, and now responsible for running Melbourne’s acclaimed Uber Lingua collective. In particular, I’m keen to find out whether he had specific priorities in mind for Clan Analogue from the outset.

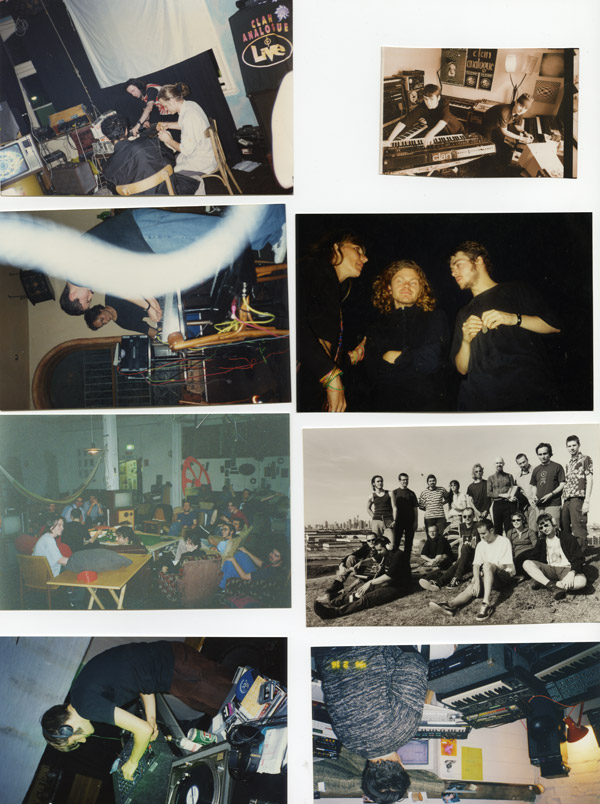

“I had been building an analogue studio inspired by the studios in Europe and the USA by the artists (whose music) I was Djing at the time,†Brendan explains. “In my teens, I’d caught the back of the acid house movement of the mid / late eighties, so was researching a number of those artists and finding many of the instruments very cheaply in Australia as the neo-analogue boom hadn’t hit yet. For instance, my first 303s cost me an average of $75. Through this process I met many synth collectors of all ages, alongside vintage organ collectors, keyboardists in bands, an ex-submariner who kept lizards and snakes and composed mega-synthy goth music with his atonal singing wife, Pete from Newtown’s music market. As I met more and more people I began to hear more and more music by people who weren’t getting the exposure they deserved. I met Toby Kazumichi Grime, who I eventually formed the band Telharmoneom with on a train station because he had a Casio keyboard under his arm, and I walked up and said hello. Toby ended up being the most supportive person helping me get Clan Analogue up and going, he did all the graphic design that pretty much defined Clan Analogue’s image. I notice that much of the imagery featured on the ‘Re: Cognition’ disc is from this pre-1995 period, even though most of the music featured on the compilation is (from) after then.â€

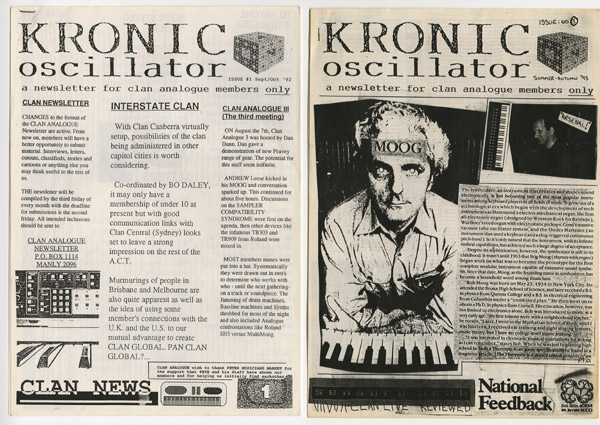

“About 20 people came to the first ‘gathering’, as they were eventually called and some of these formed the original membership of the Clan. I think only one person at that original meeting (Toby) is still involved in Clan Analogue, as the group evolved pretty rapidly over the next twelve months and other personalities started to dominate, as I started advertising in street papers and distributing posters and flyers promoting the monthly gatherings I was hosting in various places around Sydney. I worked in the UNSW Law School printing room at the time (encouraged to change the world by resident fellow, now East Timor president Jose Ramos Horta) and printed the Kronic Oscillator newsletter after hours when the head of the school wasn’t watching.â€

“People power was the Clan’s greatest resource, with most of the Sydney electronic music scene who weren’t on the Volition label getting involved on some level,†Brendan continues. “Clan Canberra started within a couple of months of the Sydney chapter, then the shortlived Brisbane crew. The Wollongong group was so small it ended up becoming the act Infusion. Melbourne started about three years in and grew into the dominant posse over the next decade. We even absorbed a copy-cat crew calling themselves The Collective, made up of mainly post-industrial bands. Clan had an ‘anyone can join’ philosophy, meaning everyone from the extremes of lefty punky electronic noise acts, and very polished and happier house music producers, to the New Romantic acts with guitars too (eek!) were in the group. Anyone who loved analogue keyboards and drum machines etc, basically. This set it up for some pretty full-on growing pains.â€

Founding Clan Analogue member Toby Kazumichi Grime remembers the early nineties in Australia being a particularly difficult time for homegrown electronic producers desperate to find live avenues, when most local venues were more receptive to rock bands, or perhaps, at a stretch – a DJ playing dance music.

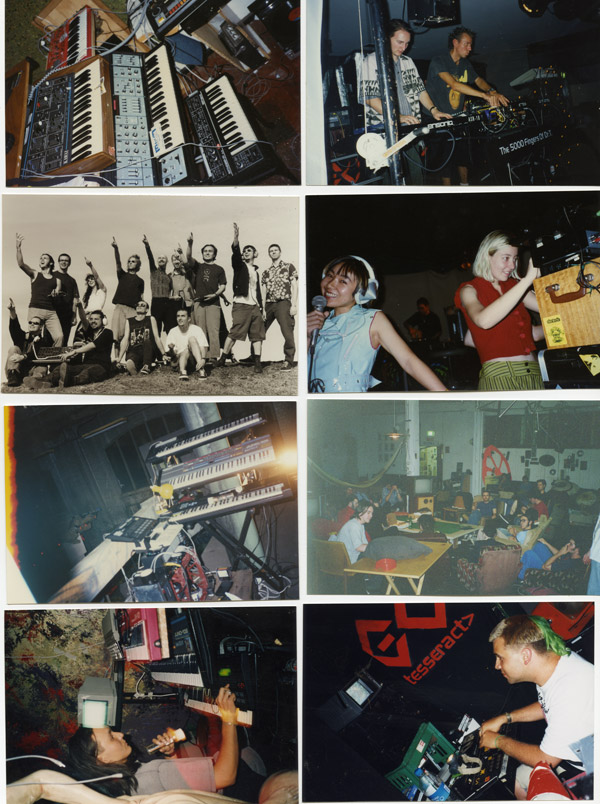

“That period in time was especially interesting,†he recollects. “The eighties had come and gone and we were in this odd crossover of post-80s EBM, late eighties Detroit techno and pre-rave era. I’d purchased and enjoyed tapes from the Cosmic Conspiracy label with bands like Distant Locust on them, but this was very much part of the avant garde underground for want of a better classification. I’d gone to many dance parties in the 1988-1990 period at places like the Hordern Pavillion and really enjoyed the atmosphere and energy. What was lacking was the live presence of electronic music – it was all about the DJ mostly and there was very little exposure of live electronic music to the masses in Australia. The perception of electronic music in Australia and particularly electronic music made by Australians was quite a grey area – it wasn’t established in any way really. It had graced us in the mainstream on occasions, but as far as a reputable electronic alternative, there wasn’t one really.â€

“Some of this attitude was compounded by the whole issue of identity in Australia, being that we prefer at times cultural influences from overseas, including music. Magazines like The Face were cultural bibles for the trendy sectors of Australian culture to namedrop one such observation, and I think we weren’t so good at accepting homegrown creativity so much. Most venues thought it quite odd, the concept of ‘live’ techno / electronic music, and (their perception of it was) almost novel, and at worst ignorant. To many, it was either DJs, rock music or pokies. The battle at this time being the rise of the DJ as ‘rock star’ and showing audiences that there was a body of people who wanted to perform techno and electronic sounds live in a club context. I remember odd conversations with people who had no idea of where ‘techno music’ came from…they’d see a bunch of us with an overzealous amount of gear and be rather confused, asking if this was how ‘DJ music’ was made.â€

“I’d found DJs like Jacqui-O inspiring,†Toby continues. “He’d been running a wonderful night at SITE nightclub called Sensoria that focused on not so much DJ music, but music by ‘bands’ that I knew. His playlist would be littered with Nitzer Ebb, Cabaret Voltaire and many other bands that I found groundbreaking at the time. This is kind of where Clan Analogue fitted in my headspace, and me having a chance meeting with Brendan at a railway station whilst I was carrying a Casio CZ101 synth was great – it all just seemed natural. I was studying photography and sound at art school and always wanted to make music of some kind. He conjured up this wonderful concept of a collective, so as we were starting to make music together, it all just flowed from there. This all started to make a framework on which these ideas of live music to an audience could take place. I’d wanted Clan to be obviously fringe and alternative with its vision and aims, which it was really.â€

One early Clan Analogue member who vividly remembers the atypical nature of live electronic performance in Australia at that time is former B(if)tek member Nicole Skeltys, now based in Pittsburgh. “Somehow I found out about a Clan Analogue gig at the Australian National University, and people from Sydney like Atone and Loose Unit came down, along with local (Canberran) noodlers,†she recalls. “It was my first exposure to 100% live electronica and I was completely blown away. One of those all too rare epiphany moments in your life where you suddenly know what your calling is, what you want to devote your life to. This was my tribe. I joined the collective when I was still with Area 51 (Skeltys’ first indie-electronic crossover band), and later met Kate Crawford at one of the many little illegal forest parties that were happening at the time and we formed B(if)tek.â€

“I was attracted by the talent of the artists, and I also dug the collective vibe – the sense of people wanting to help each other out as well as themselves. It felt like an artistic movement, not just lone egos howling for their own recognition, but promoting an aesthetic and a co-operative philosophy that I believed in. But yes, labels wouldn’t touch Australian electronica then, nor could you even get a gig anywhere. So, the fact that Clan put out vinyl and tapes, then CDs and also ran our own events so artists could perform anywhere, that was a great motivator to be involved.â€

The idea of co-operative creative enterprise as strength is something that’s also echoed by Toby Grime. “The core ideal that really made Clan Analogue a fascinating collective was the way Brendan and other members were able to pool like minded people together locally and from around the country. The network of people that had started to get involved really made the whole ‘collective’ tag a reality that worked. It kept it going and kept it fresh and full of ideas. The music releases, live events etc were really just the physical aspect of those friendships and energy.â€

“One major feature was the manner in which a collective identity was capable of attracting interest across the generations. The age differences between members was quite extreme. There would be 18 year olds and 50 year olds all centering their focus on electronic music in all its forms of process, from production to live performance and recording. They all had this common interest that brought them face to face at meetings and events. This to me was a huge success, like a spinoff of the collective being able to bridge age differences, and with that bringing different generations of music making techniques and styles. This all added great depth to the network of people and culture of the collective. This is something you couldn’t achieve through the DJ world, which is very much an age based focus.â€

While the growing membership of Clan Analogue proved to be a central source of the collective’s strengths, the rapid increase in membership also brought with it other side-effects, namely the ‘growing pains’ mentioned by Brendan Palmer earlier on. “Lefty electro-punks and the semi-commercial house music producers were not being happy bedfellows,†Brendan explains. “In the early days there were many more electro-experimental acts involved like The Family, who featured on the ‘Deep Three’ EP. Lucas Abela, who started the Dual Plover record label came to one of the meetings and argued his way onto a Big Day Out lineup. My overly socialist ‘anyone can join’ approach ironically led to Sony Music-signed Southend (famous for being sued for sampling Juan Antonio Samaranch) getting on the fourth and final EP. I remember the guy from Southend being appalled that he had to pay to be on the EP (the EPs were artist funded). This pissed off people like The Family. I remember Scot from that act saying that “it’s all about the loveâ€, as if featuring an artist signed to a major label undermined that love. He was probably right.â€

“Clan had no lefty agenda or deep desire to be commercially accepted,†Brendan emphasises. “It was a naïve construct of a middle-class North Shore kid, an apolitical united front liberating electronic sound and vision of all kinds. Turns out there were humans involved too, which brought the dream crashing down to reality, leaving its committed core elements, mostly IT professionals with music as a hobby. Clan Analogue became known to the freaks in the Vibe Tribe as ‘The Boffins.’ As time went on, the demands on Clan were greater, with many opportunities on the table. Gatherings were less about randomly jamming on piles of synths, drinking beer and smoking weed, and more about forming an association with committees, etc. This did more to drive out the more artistically inclined, which I guess was inevitable. The Canberra crew were one by one moving to Sydney and gaining more strength with their in-built political nous.â€

Palmer would himself leave Clan Analogue in 1996 to found his own separate Zonar label, with his successor Gordon Finlayson going on to substantially reorganise the Clan’s chaotic operations, to the point where the collective began to resemble a commercially viable record label more closely. During this period several Clan members such as B(if)tek and Disco Stu also began to receive substantial airplay on Triple J, resulting in greater mainstream attention being drawn to the collective’s activities.

“I’d spent almost four years pushing this greater community motivated project and I guess even when you are young that can be quite taxing,†explains Brendan regarding his departure. “I’d intentionally created a bit of a monster and in the past I’ve referred to the experience as being like daddy to over a hundred children. I needed to take this ambition of reflecting the Australian electronic music scene on another level, so I decided to leave the Clan to its own devices. I started Zonar Recordings to focus on a group of selected artists from all over Australia who I felt were uniquely representing what was going on here, including artists from Adelaide (where Clan was never established) and Brisbane (where Clan had effectively collapsed). Unfortunately I had a near-fatal car accident that undermined the development of this new business, however in the time it was running Zonar Recordings released seven CDs and the Ali Omar 12†vinyl. All excellent quality productions.â€

Toby Kazumichi Grime also remembers Brendan Palmer’s departure from Clan Analogue as representing one of the most significant turning points in the collective’s lifespan so far. “When Gordon Finlayson took on a label managing role, it shifted more to a traditional record label ideal, so there were more releases and more of a catalogue of work. This was a good time for artists to get their music out. In some ways, things got more business-like with Finlayson and his organising. It was like the second stage of Clan in a way.â€

Given that the various former and current Clan Analogue members are now scattered all over the world, I can imagine that tracking them all down to obtain tracks for the ‘Re: Cognition’ compilation must have been a formidable logistical exercise. When I catch up with compiler and current Clan label manager Nick Wilson via email however, I’m surprised to find out that it was exactly the opposite. “It actually wasn’t that hard,†Nick counters. “I put a request out to the Clan members’ email list for everyone to nominate their favourite track from the back catalogue. Then I got a selection of trusted people to listen to the shortlist and vote for what they thought were the best. Then I had a final listening session around at my place with a few reliable buddies to get the selection finalised. Because we already had all the music on earlier releases, we didn’t have to do much chasing up of people, other than for the remixes.â€

“I wanted to ensure that a wide cross-section of Clan Analogue’s history was represented, in terms of different eras and different musical styles. I also wanted every single Clan release to be represented somewhere, whether as a track on the compilation, one of the remixed tracks, a filmclip on the DVD, or something on the download-only ‘rarities’ collection. I also wanted to focus with the first disc on acts that had gone on to make a name for themselves beyond their involvement with Clan Analogue and also on those tracks that had substantial radio airplay on first release. It’s a ‘Greatest Hits’ compilation, after all.â€

“The idea of a Clan Analogue DVD had been discussed for quite a few years,†Nick elaborates. “We were discussing releasing a ‘Re: Cognition’ DVD, originally intended as a separate companion release. Martin K of Koshowko volunteered for the job of producing the DVD as he’d gained access to DVD authoring software through his work. He also had access to lots of nice camera equipment and contacts with film-makers, so he volunteered to put together a team of people to produce the doco.â€

Given that the ‘Re: Cognition’ retrospective set represents the first physical release from Clan Analogue for a few years, I’m also keen to find out more about the reasons behind the collective’s comparative absence from record store shelves in recent times. “Gordon Finlayson was keen to release a retrospective album in 2002 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of Clan Analogue,†Nick responds. “However, there was some resistance at the time from board members who wanted to focus on releasing new music, so the idea went on the backburner for a bit. Someone suggested that we incorporate new remixes so that the release included new tracks as well as the old classics, so I revived the idea and tried to get it happening for the 15th anniversary of Clan Analogue in 2007. Unfortunately, we missed that deadline due to a few reasons such as distributors closing down and various other logistical problems. But now, it’s finally out!â€

“This is the first (Clan Analogue) release after a three year break, largely due to distributors closing down, which is probably related to the move away from physical releases in the wider music industry. We’ll keep doing physical releases as long as the economics work. We see this release as a nicely packaged ‘collectible’ item in a ‘box set’s kind of way. Physical releases also give a certain sense of legitimacy to a release, elevating it above the level of demos uploaded to Myspace. They are also very effective for promotion. It is harder to sell physical product these days, but the CDs have also become cheaper to produce. We are certainly not neglecting the market for non-physical format releases, either.â€

With the second CD packaged in the ‘Re: Cognition’ set centred around remixes of classic Clan moments by a cast of producers comparatively newer to the collective, I’m keen to ask Nick whether this was a deliberate, conscious attempt to bridge together the past and present of Clan Analogue. “Yes, as noted before, there had been some sensitivity about putting out a purely nostalgic release, so it was important that new artists could get involved and produce something for the release,†Nick explains. “Several of the remixers on the second disc have not released anything previously with Clan, so it’s great to get some new people involved. It’s also a more idiosyncratic selection of tracks because it’s based on the personal choice of the remixers. The B(if)tek track ‘We Think You’re Dishy’ was requested for remixing by quite a few people, so we made that a competition where Nicole and Kate from B(if)tek chose the final selection. The runner-up remix by Bleepin’ J Squawkins was released as an extra track on the EP we put out just before the album came out.â€

With a view to to this newer cast of Clan Analogue members, I’m keen to get Nick’s thoughts about the future of the Collective. With many of the original conditions that acted as an impetus for Clan’s creation back in 1992 now substantially altered with the internet and the crossing over to the mainstream of Australian electronic music, does he see the collective’s ongoing role as having shifted along with the surrounding cultural landscape?

“There have certainly been a lot of changes since 1992,†responds Nick. “However, there are some cycles that seem to recur, for example in the early 2000s the pendulum swung back towards rock, away from electronic music, at least in the mainstream. The collective functions as a means for people interested in electronic music to come together and collaborate on projects and discuss ideas. The umbrella of ‘electronic music’ is broad enough to enable a diverse cross-section of artists to become involved. There are also aspects of electronic music which are unique in the sense that there is an ongoing and rapid development of new music technologies and ways of working. The collective is therefore a valuable way to exchange knowledge, particularly between experienced artists and people just starting out.â€

Speaking from Pittsburgh, Nicole Skeltys also sees Clan Analogue’s ongoing role amidst the Australian musical landscape as continuing to be a relevant one, even if her own direct involvement in the collective has lessened in recent years. “Well, we never made any profits from our releases, it was always more a series of art projects and trying to cover costs, so unlike other indie labels which have been going under because of the massive devaluing of recorded music and rampant download piracy, Clan can still chug along with its original vision of supporting and encouraging artistic innovation and beautiful bleeps. That said, I hope the ‘Analogue’ never leaves the Clan, meaning I hope the spirit of using the old machines live and for recording does not go away, given that so many bands now just use pre-fab soft instruments and programs and laptops to produce music. The effect is often pretty but empty – the analogue machines have souls.â€

Finally, it’s left to founder Brendan Palmer to offer the last word on where the future perhaps lies for Clan Collective, eighteen years from its formation in his Sydney flat. “I think the Melbourne crew who do most of the administrative tasks of running Clan Analogue nowadays have done a good job of keeping the quality levels at a high standard,†he suggests. “I’d like to see them do a release with all new members. However much, I know and am friends with most of the people featured on ‘Re: Cognition.’ If there’s anything I think is missing in modern day Clan Analogue it is its previous motivations to aggressively find new members and forge new territory. I guess that’s the early 1990s me speaking. Without them actively recruiting new members and trying to push the boundaries of their environment they are simply a label, an avenue to release music under a moniker that has a credible reputation forged on being progressive and active in the past. It’s their right to do that seeing they are the people who’ve stuck by what is nowadays a ‘brand’ and kept it alive. Clan is still greater than the sum of its parts.â€

Clan Analogue’s ‘Re: Cognition’ 2CD/DVD set is available now through Clan Analogue / MGM