DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid is a most mercurial of musicians, an explorer of ideals and a messer of minds. Otherwise known as Paul D. Miller, he is an explorer in the digital age, processing information through music, multimedia, the written word, and film. Based in New York, he conceptualises, sources, cuts, flips and communicates all of it back to you as his portrait of the social landscape.

Holding degrees in philosophy and French Literature and a Professor of Music Mediated Art at the European Graduate School, he tours the world lecturing, exhibiting and, among other things, recording the sounds of Antarctic ice and trying to capture the soundscape of Nauru.

Themes running through all his work are collaboration and collage, mixing and remixing. He’ll even let you remix his own work through a downloadable iPhone application. Miller was in Australia in March this year to give presentations on his latest book Sound Unbound, a collection of essays on sampling, digital music and culture in the 21st Century.

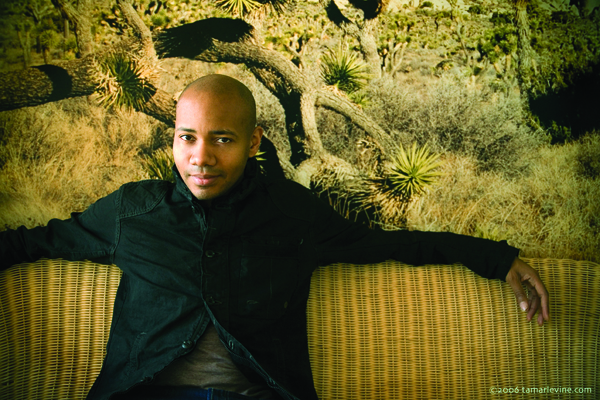

Sipping on green tea in a Paddington cafe wearing a beret, as opposed to a NY Yankee’ baseball cap, DJ Spooky aka Paul D. Miller got down to the business of explaining just why it is he has his hands spinning so many proverbial decks at the same time.

“I encourage people to be hyperactive,” he says, excitable and alert, eyes scanning the room and taking in the theatre of the street. Pointing out a man in a suit with a large leather bag, he says: “I wonder what that person’ story is, what do you think?”

Then he follows on with; “maybe specialisation and doing one thing all your life is just a different generation’ response to trying to exist in the economy of that era. It’s a strange moment here and now in the 21st century, you have to imagine that the creative, the writer, the artist – anyone who is interested in information, it is unceasing, there is a huge amount of information going on everyday, everywhere, all the time.”

“”You’re just swimming in an ocean of information. So I just kind of accept it and just feel like a fish swimming in these ocean currents.”

He agrees there are pluses and minuses to not specialising – that perhaps he doesn’ get structurally deep into any one thing. “I just kind of glide on this postmodern pond of the seductive surface of our culture, ya know?”

He pulls out his passport; a book jammed with stamps and visas, and stapled photocopies that pass for visas, and demonstrates places he’ physically traversed. He flips from interviewee to interviewer when we established we lived in Paris at the same time, delighted at the thought we may have been swimming in the same current at the same time.

A school of interested aquatic types turn up to Ariel bookstore in Paddington on a Tuesday night for his presentation of Sound Unbound. Curators, journalists, musicians and even photographer Spencer Tunick, he who can get thousands of people naked for a photo, mill about in between aisles of books expectantly.

Miller thanks everyone for turning out, introduces himself and others in the audience, already making links and supplying connections and begins “Welcome to the Sydney – New York remix, here we go!â€

Miller has connected a diverse array of people, or “36 egomaniacs” as he calls them, who present us with their ideas on sampling, digital music and culture in the 21st Century. Sound Unbound seats Brian Eno next to Moby, Chuck D next to Steve Reich and Scanner next to Daphne Keller.

“Think of it as a virtual dinner party, or maybe like one of Spencer’ “happenings’ getting a whole bunch of people together, naked, who would never normally be in the same room.” Sound Unbound jumps and cuts between diverse ideals from diverse voices and the main thing that connects the stories is Miller’ notion of the “collage aesthetic’.

Fittingly, the book Sound Unbound comes with a CD soundtrack selected, mixed, scratched, re-worked and produced by DJ Spooky. It takes classic works and words you know and repositions them to music you may also know. Miller takes a host of pieces from the Sub Rosa label, a Belgian record label which has released celebrated avant-garde artists since the 1980s. Diving into the label’ catalogue he has selected works classified by the label under “Aural Documents’. Works by Marcel Duchamp and William S. Burroughs are read by Iggy Pop and even James Joyce’ reading of Ulysses are blended with electronica from musicians including Bill Laswell, Aphex Twin and lauded composers Ryuichi Sakamoto and Phillip Glass.

With 45 tracks there’ room for a bit of exploration on the experimental side of the pond, and you’ll even hear a DJ Spooky remix of Sonic Youth’ “Audience’ and “Hommage a John Cage†from Nam Jun Paik. “The whole pun here is that the CD is like a kind of literary collage in its own right – so you “read’ the CD and “listen’ to the bookâ€.

You’re on notice here; DJ Spooky wants to expand your mind, create new synapses in your brain and take you swimming through the oceans he’ spent time in. Surfing on sine waves, indeed.

A repeated theme throughout the collection of essays, not unlike a squelchy TB 303 drum loop in your favourite electro track, is the use of new and ever-evolving technology that gives almost anyone quick and relatively easy access to tools for creating.

New technology allows digital kids to take unconscious clues from movements like early 20th Century Dadaism and its collage culture to, in the words of Daft Punk; “cut it, paste it, save it, load it, check it, quick re-write it”.

Taking from the ideas of others and building on them, mixing them or reinterpreting them is essential to the evolution of art, science and even culture – but when the lines get blurred and ownership of ideas is questioned, copyright law inevitably rears its controversial head.

Daphne Keller, who contributes the tantalizingly titled essay “The Musician as Thief: Digital Culture and Copyright Law’, is Senior Products Counsel and the lead attorney responsible for analysing copyright and related legal issues at Google.

Her essay in Sound Unbound tells us human culture is always derivative and maybe music is more so than other art forms. “We hear music, process it, reconfigure it and create something derivative but new – folk melodies become Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies…Rodgers and Hammerstein’ ‘My Favourite Things’ becomes a John Coltrane classic.” There is a long history of music being re-interpreted or re-worked and brought to a wider audience in the Before Google (BG) age.

Take the hot, sweaty dance floors of New York clubs in the 70s, with Grandmaster Flash keeping people grooving while perfecting his “Backspin Technique’ under the flickering lights of a disco ball. By using duplicate copies of the same record and a mixer he could isolate the same fragment of music on each turntable and extend that fragment in the record indefinitely by switching the mixer between records, extending the groove.

Instead of passively spinning records Grandmaster Flash invented techniques to create new music and the art of turntablism was born. “The beginning of hip hop was about playing familiar sounds that were taken out of context, Grandmaster Flash did that back in the day” says Miller.

Keller’ essay explores the current state of US copyright law in relation to music, sampling and hip hop. Keller discusses the clause in the US Constitution granting limited rights to authors to “Promote the Progress of Science and Useful Arts” and how it could, in theory, be applied to the cultural practice of sampling. She mentions famous court cases and out of court settlements that have tried this tact and failed, notably the first sampling case in US history, the Biz Markie case in 1991.

The referral by Judge Kevin Duffy for criminal prosecution for Biz Markie’ sample of Gilbert O’Sullivan’ “Alone Again’ changed the hip hop music industry and required any future sampling be cleared by original copyright owners. Keller argues copyright law needs to stop lagging behind cultural change and technology shifts in music to “Promote the Progress’ in the Google age.

With the onset of digital technology, the After Google age reels of heavy, bulky magnetic tape containing music could be converted to an MP3 file and downloaded on the other side of the planet in a matter of seconds.

Take that newly uploaded MP3 file, and software allows you to isolate snippets of songs digitally, grab them and replay them wherever you like. You have created a “sample’. “Music is one of the most elusive aspects of our culture – it vanishes into thin air- but it leaves a trace. So manipulating memory has become part and parcel of sampling,” Miller says.

With sampling in the digital age you can hold a series of sourced sounds in your hard drive and create a new composition out of bits of other people’ songs in moments, which is what experimental sound artist John Cage, an inspiration to DJ Spooky, did in the analogue era with tape. Although it took Cage a year to record and splice untold reels of tape to make his famous “Williams Mix’ – which at just four minutes long only just eclipses the quintessential three and a half minute pop song.

But artists selling new digital compositions of found sound could be criminal according to current copyright laws. “I’ve never been sued,” Miller tells his audience “because I rework samples so intensely that they become virtually unrecognisable.”

Many hip hop artists were directly affected by the landmark copyright ruling against Biz Markie, including Public Enemy. “If you look at Public Enemy’ first album it’s an amazing chaos of sound and in fact you couldn’ make an album like that anymore because of copyright law.” says Miller.

Public Enemy has always embraced new technology in its politically charged music and in 1999 signed to the independent, web savvy Atomic Pop to be one of the first artists to release an MP3-only album, a format relatively unknown at the time.

Public Enemy are currently using another web-based project “SellaBand’ to fund its upcoming album. SellaBand invites fans of artists to donate capital to help musicians fund new albums and the slogan of the company is “We Believe in the Freedom of Music.” Chuck D, Public Enemy’ lyricist, has a powerful, booming voice; the kind that makes you sit up and listen, like a believer in a pew listening to a preacher at the pulpit.

A teenager growing up in Sydney’ suburbs now is just as likely to call back “Fight The Power” to Chuck D as an African American teenager would have in Brooklyn in the 80s. ‘Fight the Power’ is regarded as one of the most popular and influential songs in hip hop history and calling along to the chorus for followers of hip hop is like punctuating a prayer with “Amen’. Even if you don’ know what the power is you’re fighting, you know from the strength and depth of Chuck D’ vocals backed by Public Enemy’ beats that something big is going down.

Chuck D’ contribution to Sound Unbound is “Three Pieces’; an article titled “A Twisted Sense of God’ and two rhymes, “Hip-Hop vs. Rap’ and “Rap, Race, Reality and Technology’. “Rap, race and reality and technology set you free” is the way Chuck D writes the introduction to his final rhyme in Sound Unbound.

The written word and copyright gets a look in too in Jonathan Lethem’ essay, “The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism Mosaic’. Lethem is a New York Times best selling author and brings to Sound Unbound the idea of “gift economies’ and cryptomnesia. He begins with the synopsis of Vladimir Nabokov’ Lolita – as described in Heinz von Lichberg’ story published 40 years before Lolita. Lethem asks: “Did the earlier tale exist for Nabokov as a hidden, unacknowledged history?” Or, spun another way, did Nabokov write Lolita under the phenomenon of “cryptomnesia’?

“Art that matters to us – which moves the heart, or revives the soul, or delights the senses, or offers courage for living however we choose to describe the experience – is received the way a gift is received,” he says.

Miller puts the idea of the “gift economy’ into action as part of his presentation and hands out mixes to everyone of bits and pieces of his latest music. “I’m hoping everybody, instead of just being passive and just pressing play, you’ll go home and make mixes of this and send those mixes to your friends”.

Don’ despair if you weren’ there. You can always, like “75,000 people have since Christmas” download the iPhone application and get mixing. It is a basic DJ set for your phone, complete with a mixer, samples of scratching, synth loops, drum patterns and songs from the DJ Spooky release of last year The Secret Song.

“There is an update coming that will let you import your iTunes library and record your mixes, but right now you can visually beat-match music on a mobile platform – forget bringing records anymore, now it’s all about sound files and doing DJ tricks on your phone.”

Miller took a mobile recording studio to Antarctica to do a “sound portrait’s of the continent by recording the sound of ice – “TERRA NOVA: Sinfonia Antarctica’. “Antarctica itself is a document, it has millions of years of history, you dig down into the ice and the call it “core sampling’,” he says. “””Sampling’ here is actually a scientific termâ€. Miller toured the multimedia installation “Sinfonia Antarctica’ globally through 2009.

The next multimedia project took him to Nauru with architect Annie Kwon to create “Nauru Elergies: A Portrait in sound and Hypsographic Architecture’. Miller teamed up with Finder’ Quartet to perform Nauru Elergies at Shed 4 in Melbourne’ Docklands as part of the Experimenta Biennial.

“Sound is one of the hardest things to quantify in our culture as the dominant media of our time is visuality.” By witnessing the combined visual with the aural for this project we are invited to meditate on the bizarre colonial and economic history of a remote Pacific island.

Signing copies of his book at the end of his presentation, Miller plays the conductor, consciously connecting people who stick around. Introducing new people he’ met to old associates who he thinks will spark, striking up conversations, inviting those around him to follow his lead.

As we walk down Oxford St, we pass an accordion player outside a cinema in a striped Bretagne t-shirt and red kerchief. He’ an entertainer for French Film Festival goers and his presence evokes shared memories of Paris. Miller, adjusting his beret, says “I feel a deep sense of connectedness to all the information around me and I think my writing and my music reflects that.” Hmmm spooky.

Sound Unbound is out now through MIT Press.