At the end of the 1980s, I remember as a black clad teenager flicking through the “experimental’ CD racks at Sydney’s Red Eye Records and coming across these releases with a distinctive red band across them – the design signature of Melbourne’s Extreme Records. Like many others, this was my first introduction to Bryn Jones’ experiments as Muslimgauze, and later Merzbow. As the ’90s wore on, various Extreme releases crept their way into my collection – Stefan Tischler, David Thrusell’s Soma project, C-Schulz and Shinjuku Thief, amongst others.

In 2000, the label released a 50 CD box set called the Merzbox and then in 2003 the label disappeared as a result of distribution problems. Then one day in 2006, a package of new Extreme releases landed in the Cyclic Defrost letterbox for review; Extreme was back, with a shifted focus to concentrate more on releases by local Australian artists.

Extreme’s Roger Richards explains, “I love the creativity, energy and commitment that is shining through in Australian music at this time. My hiatus from new releases gave me time to step back, see what was happening elsewhere and jump back in with the knowledge that what is happening here is special. The music industry isn’t making it easier yet these musicians are prepared to go out on a limb to offer their true musical expression to the world. Of course, Extreme needs to go out on a limb too and I embrace getting outside of my comfort zone. I could suggest this is madness in this current sales climate but the effort is definitely starting to pay off and the music is fantastic!”

“Australian music often flies in the face of fashion, offering something truly amazing and inspiring. Perhaps this is partly due to our isolation but I would suggest that it is something inherent in our culture, that we are prepared to take a chance and stay true to our vision. What I have seen change is the global influence on music and the fragmentation of styles that have emerged. [Throughout the 1980s] Australian groups like SPK, Foetus (Jim Thirlwell) and Severed Heads were a major influence on alternative music, however, it is more likely nowadays that a dance act, ostensibly more commercial, will fly the flag for ‘alternative’ Australian music and whilst I certainly acknowledge the great rock music that Australia has produced, it would never be on Extreme.”

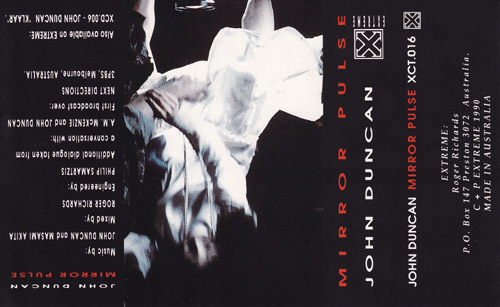

The history of Extreme begins in the fertile 1980s. “The label was started by Ulex Xane in 1984 as a cassette label releasing industrial and power electronics. Ulex was active in the international underground tape network, releasing and distributing music from Australia and overseas, and I became involved when I saw a flyer in a record store. Having just arrived in Melbourne, I was excited to see that someone was making this kind of music available. At the time there was a lot of great independent rock music and the new music scene in Melbourne included the likes of Ollie Olsen and John Murphy, some of whose releases were put out on cassette. Not long after I met with Ulex, I started helping out with mailing out cassettes and organising gigs. It was after a festival in 1987 that Ulex decided he wanted to scale back from the label side of things and concentrate more on his own music. At the same time, I was keen to see Extreme gain a greater profile and change the image from industrial to experimental and new music so the label you see today started from there.”

Extreme’s rise to broad international prominence came through some of the earliest international releases from Merzbow and Muslimgauze. “With Bryn Jones and Muslimgauze, it was a case of already distributing his records. We had been doing so for some years, since 1985, and having this relationship meant we were both wanting to see an album (or six) released. I went to meet Bryn in Manchester in 1990 after we had already agreed to release Intifaxa (1990), and we decided to take it further. The recording contract resulted in United States of Islam (1991), Infidel (1994), and Zul’m (1992) . . . In the case of Masami Akita, I had been a big fan of Merzbow since the early ’80s. I bought his debut LP Material Action 2 of 1983. I first started reissuing some of his cassette albums on Extreme and we have been friends since then. Thus when I finally decided it was time for Extreme to release an LP (rather than cassette), it had to be with Merzbow. At the time, he had an ongoing collaboration with S.B.O.T.H.I. a project of Achim Wollschied, a sound artist. This project was initiated by Jonathan Walker to produce a single to be published in Art Australia. But since I knew Jonathan, it was the perfect opportunity to extend this collaboration. The record was the first and last vinyl LP on Extreme.”

“The Merzbox is an entirely different story. It all started as part of a plan to celebrate 10 years of Extreme and grew from there. I already had so many cassette releases from Merzbow that I had already reissued or wanted to reissue so I suggested this project to Masami. He explained he had the same feeling about a lot of his earlier music and also that there were some amazing albums as yet unreleased. The total quickly grew to 50 and we had to stop it there! We spent many more months working out what those 50 CDs would be. Of course, now I was bitten by the idea of a boxed set, I figured it had to have a book, artwork, CD-Rom, t-shirt, special packaging and of course a commemorative “Merzdallion’. The whole project took four years and involved a core team of seven people, along with all of the people who would visit on weekends and help pack the Merzbox full of goodies!”

Labels like Extreme emerged at specific time between formats – at the time in the changeover period between vinyl, cassettes and CDs. This time around, in the format shift between CDs and digital files, there is a much more complex process of disintermediation to be grappled with. The disintermediation of music made possible by digital distribution effectively offers to connect artist to listener, and other listeners to each other – bypassing the traditional gatekeepers and intermediaries – record labels, their distributors, and the music press. Of course, it isn’t that simple. Rapidly falling prices of music production equipment has resulted in a glut of music which conversely increases the need for new intermediaries, which is where the rise of online recommender services, online social networks, and niche blogs are replacing the old world of print media, face to face record stores, and traditional distribution. Likewise, as the biggest bands make the final transition into “brands’ and their releases become ‘advertising’ for their expensive live shows, the impact upon niche music scenes in which ‘live’ performances are rare and releases act as social documents, is unknown.

“I think the emergence of digital has had the initial affect of reducing sales of CDs for Extreme’s more unknown artists. I don’t think this is simply a digital phenomenon, it’s also to do with the multiplication of labels and, of course, the ease at which music can be produced nowadays on computers. With quantity and availability, free music and downloads, the market has become saturated and the music listener has too much information to sift through to find the new music. This has certainly caused Extreme to think long and hard about marketing, with a far more focused approach as a consequence. It has also provided a further incentive to challenge me about what Extreme will look like in five to 10 years time. I am pleased to see the sound quality of MP3s improving and I envisage that one day digital downloads will sound better than CDs or LPs! I would hope that a label like Extreme could emerge in this context. It’s an interesting question. I would suggest that it might be the consequence of a new style of music being picked up and brought to the world’s attention through both alternative and mainstream media. I don’t believe the cost of marketing through traditional means, such as advertising, would be justified. What is the experimental music of today often diffuses into the mainstream of tomorrow and where this new style starts is often from an experimental musician and label.”

Find out more about Extreme at www.xtr.com.