Last year, a reclusive young Kansas musician recorded an album with a peculiar creative motif and weathered, fragile instrumental beauty. It was called Almond and it was released on Sydney label Preservation. It was one of the most stunning debuts of the year; tinged with artefacts, emotions, politics and memories, instruments, objects and talking toys. But where Almond predominantly dealt with times past, Martin’ remarkable second album River Water — released this October, again through Preservation — immerses itself in a stark, introspective and achingly beautiful present.

Aaron Martin’ sparsely looped arrangements inhabit a strikingly disparate space; where a distinct production and compositional sensibility is pressed against a vast, echoing vision of a decaying American Midwest; where the rendering of vivid emotions and recollections weren’ limited to words. Aaron Martin lived a solitary childhood, there were no long-time school friends, no lasting sense of familiarity. Born in Denver, Colorado, he spent his pre and early teen years crisscrossing the Mid-Atlantic, South and Midwestern states—from Colorado to Pennsylvania, from Pennsylvania to Florida, from Florida back to Pennsylvania, and finally, from Pennsylvania to Kansas.

And it wouldn’ be unfair to assume that such a dislocated early life had lasting effects on the 25-year-old. “I tend to shy away from people,†he offers simply, speaking from his current home outside of Topeka, Kansas. “Even as a kid, I liked to keep to myself, and only had a few close friends. Since my family moved so much, it was hard to make connections with people… We were never in one location for very long.†That’s not to say that there weren’ good times for the young Martin, namely his family’ second stint in Pennsylvania. “It was probably the most social period of my life,†he says. “We lived there for about five years, so I was able to make some friends and really settle in to one location. We had a couple acres of land, so I spent a lot of time outside with my friends, climbing trees, riding motorcycles, jumping off of the roof onto a trampoline. We just went wild and had fun. There was an exuberance to those few years that I had never experienced. A lot of the memories that I draw from for my music stem from my years in Pennsylvania. When I moved away from there to Kansas, when I was thirteen, it was a difficult transition, my personality shifted; I turned inward.â€

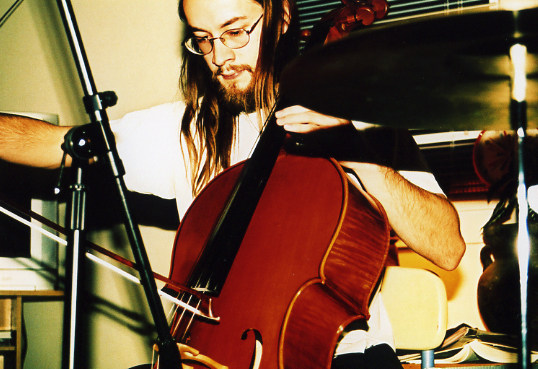

Personal reminiscence plays a huge part in Martin’ unique strain of music making. Using a loose tangle of instrumentation (cello, ukulele, organ, mandolin, recorder, glockenspiel, various guitars, whistles and percussion), a looping pedal and an expansive cache of various other “materials’ (CD cleaner, ice bag, shampoo bottle, camera, alphabet school bus, bowed light fixture, comb, pocket watch and laughing turtle, to name a few on Almond), Martin’ austere instrumental arrangements weave a dichotomous but nonetheless evocative web of hints, traces and artefacts from his past and present. “Memory plays an important role in my music,†he explains. “I am drawn to the idea of capturing feelings evoked by events in my life that have had a strong impact on me. Obviously, many of those experiences occurred during my childhood.â€

The effect, so stunningly articulated on his debut record Almond, is both naïve and considered—clearly emotive and immediate in its creative foundation, but undeniably philosophical and measured in its compositional approach and qualities. “Music is a way for me to make observations about what I have experienced,†explains Martin. “Each piece is tinged with emotion and often paired with layers of thoughts that I have gathered. This is the approach that I feel is most natural for me. It is very personal, which has advantages and disadvantages. It makes me vulnerable, but also allows me to express myself in an unadorned way.â€

Martin has a largely intuitive musical history. Having never really listened to music as a child, his interest was sparked when a school friend invited him to play the guitar as an accompaniment to his drumming. Suffice to say, it was something of an epiphany for the 11-year-old. “I finally decided to give it a try,†he recalls fondly. “From then on playing music became a natural extension of my personality. I didn’ have a strong connection to particular artists or songs…I just developed this real desire to create music, rather than to listen to it.â€

After dabbling in guitar and drums throughout his mid-teen years—“just for fun,†as he puts it—Martin’ musical bearings really began to take shape when he started learning the cello at 17. “For some reason, I had it in my mind for a long time that I wanted to play cello,†Martin remembers. “I had never played one before, and didn’ even know how to read music, but I decided to rent one from a local music store. I was determined to learn how to play, even though cello is a difficult instrument, and most “classically trained’ musicians start at a much younger age.â€He became obsessed with chamber music and began frenetically consuming the works of minimalist Estonian composer Arvo Pärt and the playing of British cellist Jacqueline du Pré; artists whom he still credits as having an impact on his artistic vision. Quite incredibly, within six months of starting lessons, Martin was playing in a local youth orchestra. Even more remarkable was the fact that after just another year, he was accepted into college as a cello performance major. “It was a crazy process,†laughs Martin. “Being thrown into a formal music setting was overwhelming at times. I learned rapidly, but also felt confined by spending the bulk of my time interpreting music.â€

While studying cello proved an intellectual challenge, Martin found creative solace in toying with the idea of writing his own compositions. His impetus to really apply himself to this process came with a friend’ short film project, which was in need a score. “I bought a used four-track, I really enjoyed that process, and ended up recording music for several more of his films. At that point, my music began to really take shape. I used every instrument and object that I had access to. Eventually, I bought a digital recorder, which I still use, and I recorded five CDs of music before Almond, which I gave out to a few friends and family. I never expected anything I recorded to be released in an official way. I bought a looper pedal about a year and a half ago simply as a way to play live,†he continues. “Repetition had played a major role in the music that I recorded before I started to use loops, so the pedal became the perfect tool for me.â€

Martin, who was living above a retirement facility for Vietnam veterans at the time, began piecing together the compositions that were to become Almond. The strange surroundings played quite a part in the record’ direction. “It was a strange environment to live in,†says Martin. “Most of the residents had severe psychological problems, and I had some odd experiences there, which greatly affected the music I recorded. While I think of the album as the summation of years of memories, it also captured a moment in my life when I felt most uncertain. I wasn’ comfortable with where I was living, and was in an awkward transition after graduating from college. Each piece of music is a thought I was lost in.â€

Such tensions are clearly evident in Almond‘ lilting, American folk-inflected compositions. While Martin’ arrangements revolve around elegant central instrumental motifs—such as the whispered interplay between ukulele, banjo and cello on “The Ducks Are Just Sleeping’ and the stunning layers of organ, percussion and strings on “Canopy’. A darker stream of scurrying, rumbling and scratching undertones permeate the yearning minor-key melodies of tracks like “Kentucky’ and “Bare Hands’. It’s something that Martin sees as crucial to his music. “It’s important for me to shade the music with layers of meaning,†he explains. “It’s not enough to record something beautiful. Every element present is there for a reason, and has been carefully considered. I’m interested in creating music that has both clarity and complexity…so that, even though the parts are often stripped down to their bare minimum, there are shards of meaning that spring up all over the place. Sometimes they butt up against each other, and sometimes they work alongside each other.â€

One of the record’ most interesting applications of this idea is in its use of children’ toys. Indeed, the aforementioned “Canopy’ and “The Ducks Are Just Sleeping’ offset their ornate melodics with garishly distorted loops of children’ toys—a talking school bus and a laughing turtle, to be precise. But while somewhat discordant, the toys add another evocative layer to the songs’ individual aural narratives. For Martin, the toys represent just another interesting piece of instrumentation. “I use toys just like I would any other texture,†he says matter-of-factly. “They can add richness and spontaneity to music, but I think they require special consideration, so that they don’ come off as being used flippantly, or give the music too much of a cartoonish quality. It’s always intriguing to take elements that seem outlandish, and to put them into a meaningful musical context. There is normally a psychological component to what I add to a piece, in terms of implying meaning.â€

A particularly telling track is “Water Damage’, where a swelling chorus of ukuleles, plucked strings, tambourines and spindly keys underscores a spoken-word sample of a television program, with a group of late middle-aged men shooting the breeze about American values, turkey hunting and animation whilst waiting for a bite out on Lake Michigan. It’s a fascinating document, which offers an equally endearing and troubling portrait of contemporary America. Martin, however, is cautious about imposing any kind of definitive meaning on such tracks. “Most of the pieces on Almond are making some type of statement,†he posits. “I wouldn’ say that it’s my role to dictate how people should interpret those statements, but from time to time I make cultural observations.â€

“It’s never my intention to take cheap shots, or even to make statements about America that have one clear-cut meaning,†he continues. “”Water Damage’ has an interesting history; the original version used a different sample, which I wasn’ able to use for legal reasons, so at the last minute I had to try to figure out how to make the piece work without it… Luckily, I remembered that I had another sample on my pedal that I thought might work, and it ended up complimenting the piece perfectly. Both versions of “Water Damage’ point to an element of American culture that is simultaneously amusing and disturbing. For some reason, I am oddly attracted to the contradictory nature of that.â€

Martin’ new record occupies a very different space, both in terms of its conceptual orientation and musical application. Where Almond peppered its instrumental motifs with scattered array of aural flotsam and jetsam, River Water sees Martin give his instrumental layers more room to breathe and develop. The results are stunning, with Martin’ austere cello and banjo arrangements resonating with a far deeper, more harrowing, sense of emotional candour and nuance. “I wanted to explore how a mood shifts,†he offers. “This is a complicated endeavour, and one that I was unable to examine with Almond, because the way I recorded it inhibited my ability to create transitions. So, with River Water, elements are often set in place, then dragged under, while others remain, or a whole new set of ideas emerges, causing gradual or more drastic shifts in mood. It’s an album about transition, about a constant effort to get to the core of things, both emotionally and musically.â€

Indeed, while Almond often inhabited an observational and artefactual realm, as Martin explains, his new work delves toward a more densely speculative and internal sensibility. “River Water is predominantly introspective,†he pauses. “Almond had glimpses of this, but also dealt with broader issues and observations. Memory still plays a key role in the music—and most likely will continue to—but this album is more about processing memory in the moment of remembering, in an attempt to bring some type of clarity to the current state of things, rather than actually transporting oneself back to an event in the past.â€

Having moved out of his apartment above the retirement facility after completing Almond, Martin recorded River Water in a room of an old house that he, his father and younger brother were renovating. Although tracked sporadically between November 2006 and July of this year, the recording and thought process behind the record was far more focused and economical than its predecessor. “I used the same equipment that I used for Almond,†says Martin. “Everything was recorded in long takes without using a computer or any effects other than loops. But there are a couple key differences between how the two albums were recorded. Almond was a document of pieces that I had been playing live, and I wanted to capture the music in that context. Because of that, I was limited to using loops exclusively and in a very specific way. Also, all of the pieces existed before they were recorded. I felt like locking myself into working that way would be too restrictive.â€

“For River Water, I wanted the freedom to create a variety of shapes or structures, rather than being confined to one general arc. In addition to that, with the exception of a few pieces, I created the music as I was recording it, which I much prefer as a method of recording. I think it really freed me up to hone my sense of structure,†he continues. “I am unendingly striving to express myself in a very concentrated way, where all of the elements in place are essential, and the result is both something concise and complex.â€

It’s a just summation; while Martin’ compositions prove increasingly spare in terms of instrumentation, materials and motif, River Water‘ thematic and emotive undercurrent is densely psychological and evocative in effect. It’s an incredible combination, from the echoing percussion and tender ukulele and cello interplay of opener “Alison’ and the stark, toll-like mandolin and menacing string section of “Sisters’, to the yearning banjo melody and abstracted vocal layering of “Cord Blood’ and the wondrously childlike recorder chorus of “Burning Honey’. The haunting strings of “Tire Swing’ and vocal-stained desperation of “Trees and Smoke’ that add an overwhelming sense of vulnerability to the record, while the subtle underscore of field recordings on “The Shape of Leaves’ and “Tar Paper’ encroach on a powerful place-based dynamic, as if echoing with the heat and humidity of the Midwestern summer.

For Martin, the album’ effectiveness rests in his increasing musical responsiveness to his own material—in allowing the songs to “tell’ him what they need instrumentally and to interpret their signals in a sensitive way. “I just wanted the musicianship to be as focused as the conceptual elements at play,†he says. “It’s hard for me to describe the evolution of instrumentation for particular recordings, because every piece uses a different set of materials unique to the logic of its structure. I did want to explore sounds that I hear day-to-day by working in some field recordings, which show up on “The Shape of Leaves’ and “Tar Paper’. It’s important for me to investigate my environment, and try to come to terms with it, as well as understand how it shapes my general mood.â€

And as he explains, this environment was far from stable. “This past year was a transitional period for me. After moving out of the retirement home, I spent a lot of time working with my dad on the house where I live now. It seemed like an endless process. During this time, my older brother moved into a different house, and so did my parents. So, we were all uprooted at once, and trying to get our footing again. When we finally got settled in, our basement completely flooded. So, part of the turbulence present in the album is due to those circumstances. Also, going from not thinking that any of my music would ever be released, to getting a number of musical opportunities was another transition, which caused a general feeling of excitement and disorientation. I think more than any specific event, though, River Water is a product of a general search for clarity—trying to come to terms with memory and the state of existing as a human being in order to move forward in a meaningful way.â€

And as Martin explains, this way forward is one to be taken alone. “It would be strange for me to want to bring in other musicians,†he says, “it would be like having multiple writers contribute content to a poem. Even if the end result was more refined, the vision would be diluted.†But for the unassuming Martin, just the fact that his unique musical vision even has an audience is beyond his comprehension. “I don’ think I’ve quite adjusted to the idea of having listeners, even in a limited capacity,†he laughs. “I’m just happy that people have the opportunity to hear it.â€

River Water is available through Preservation/Inertia.