David Toop is a UK musician and intellectual who practices a form of sound art that always skirts the boundaries of the possible and the impossible. He has worked in many fields of music, sound arts, curating and writing. Having released 26 Albums, published 5 books on music with another to be released next month, worked as a music journalist (for crimes committed in his youth;-), along with his impressive community service as a public intellectual lecturing at the London College of Communication where he holds a professorship as the Chair of Audio Culture and Improvisation.

Innerversitysound: Your latest album has within it a section that references part of the art of Japanese Garden arranging. In some senses this can be seen as an excellent metaphor for your interest in collating diverse threads and arranging them into form. Can you tell us a little about your gardening practice and how you conceive of this particular season’s arrangement?

David Toop: I have been fascinated with Japanese gardens for a long time. In all of my visits to Japan I have tried to see different gardens, a good example is Ryōan-ji, a famous garden in Kyoto, I have seen a number of times. So that lead me to create my own Japanese garden in my previous house and to research the role of sound in Japanese gardens and to research the fundamental principles of Japanese gardens. One of the interesting things in this notion of stone setting, which goes back a very long way in history, to the point where the significance of where you place things within the garden was related to various taboos. Is that to me there is a similarity between that and musical form. So the way you divide up a piece, the proportions of that division have a relationship in my mind to the way you think about and arrange stones in a Japanese garden. And it’s a difficult thing, I remember when I made a Japanese garden, I finished pretty much everything, the landscaping and planting, I tried to set three stones and it took me a long time of just placing them and replacing them. Trying to find the right, what felt like the right, configuration, distance and so on. It’s not dissimilar to working within the computer and structuring a piece of music in the way that I do. I think it’s possible to cross over, to create a kind of fluidity, between these apparently dissimilar practices and in a way that’s the basis of a lot of my work now. To create a kind of transferability between two activities that seem to have a very obscure or slender relationship to each other.

I suppose on a personal level it’s about thinking about how all these different obsessions, fascinations, personal activities, how they connect to one another. So if I am thinking about a garden, what are the connections between that and sound music. I suppose one obvious connection is listening practice. There is something in gardening, if you are gardening in terms of all of the senses, something very important about the sounds in the garden, whether it be from living creatures or plants or whatever. This piece you are talking about, stone setting, the sounds in the piece, other than the narration by Mariko Sugano and the flute playing by Emi Watanabe, is the sounds of a pond I made in the new garden, sounds recorded with a Hydrophone in the pond. It’s very interesting to me to make these connections, there are these connections with the two people that play on the track, one reading, one playing. Which go back years, so that’s a personal thing for me and then they are brought together with the sounds of water insects and creatures, and so on, that are living below the surface of the water in the pond. So you see how all of these things in my mind become intertwined. I suppose it’s the feeling of how life is lived and trying to get beyond this idea of that everything in your life is somehow compartmentalised. And in fact making a pond is perhaps a musical gesture and maybe making a piece of music is a gardening gesture.

David Toop – Dry Keys Echo In The Dark And Humid Early Hours from ROOM40 on Vimeo.

Innerversitysound: To my ear it sounds like you have moved away from Logic Audio and are now using MaxMSP.

David Toop: No, I am still in Logic. Actually some of the material is transferred to Ableton Live using MaxMSP in Live and transforming things in that way and then taking them back into logic. And I work with a couple of other editing programs as well. So there is a back and forth movement and to be honest it is to such a degree that I forget what has done what.

Innerversitysound: Also you seem to be collating a great deal of sampled sound as well as experiments in instrumentation, the oblique application of sound tools and the possibilities of sound. Can you describe your contemporary practice, the rituals of daily performance and the tools you are using to create your sound? How do you see the appearance and practice of your art form changing in the near future?

David Toop: Yeah, those are very interesting questions but can I backtrack to your first statement which was about sound samples and I wonder where you are hearing those or what you mean by that.

Innerversitysound: You are saying that you are not using sampled sounds in your work, that I can’t hear sampling of your rather large collection.

David Toop: No I don’t think there is any at all. It’s all either sounds I’ve made or things I’ve played or there are guest musicians on a few tracks. So for example the saxophone playing on two tracks is by John Butcher, the sarangi playing is by Sylvia Hallett, there is Emi Watanabe playing the transverse flutes, Rie Nakajima is playing small battery operated percussive things with me. I am trying to think of anybody else. I did record Rodger Turner playing drums and reconfigured, I don’t like to call it sampling but reconfigured what he played into percussion patterns. But that’s a bit different from sampling to me. There’s quite a lot from my personal history of making sound but that’s a different story as well. Back to your original question, the way this record was made, the way it was put together was that I was in Cornwell actually. I was there intending to write. I had been asked to write an autobiography for a Japanese publisher and I went to Cornwell for a week to get started on it. I didn’t really write a word but what I did do was started listening through to a lot of pieces or sounds I had made over the previous four years, five years maybe. And there was a lot because I had built up this backlog, simply because I hadn’t released anything for such a long time. I started to put things together and thinking “yeah this sounds like the beginning of a record” and by the end of that week in Cornwell I had put together the basis of a record. So then it was just the question of coming back to London and working with the musicians I had mentioned to add an element to the pieces.

I tend to make sounds by recording instruments or actions of some kind and what I mean by instrument is anything from a conventional instrument to a piece of paper and then transforming those. They go through different iterations over time and very quickly I forget the original source material. Then I put those together in some way, maybe Logic, or Live, and they become a piece and then that piece can become part of another piece. So pieces become pieces and that is very much how this record was made. All of that relates to what you call daily rituals in an important way. So for example I practice guitar every day and what I practice may have nothing to do with what I play in performance. But it’s very important to me. And one of the other things I did when I went to Cornwell is drawing. Drawing is something that was very important to me when I was a teenager and gradually atrophied as my focus moved away from visual arts into music and working with sound. I have tried to regain that connection with drawing in the last few years and it’s been quite a painful business because every time I’ve made a drawing I’ve felt that it was really terrible. So I basically throw them away. And what I’ve been thinking about more recently is the question of can drawing be a musical instrument. This is similar to what I was saying about the relationship between Japanese gardens and the practice of making music. Can there be a fluidity, can there be a crossing over of the natural boundary that seems to exist between the practice of drawing and the practice of working with sound. This is something that I have developed as a theoretical idea and as an idea in practice. In various ways, some of them practical, you know actually working with what you may call action drawings.

I work with a Japanese artist called Rie Nakajima whose work appears on this record. We do performances together and we do collaborative performance event called Sculpture. In our duo performances we have started making drawings together which are the result of actions of a certain kind. So that in a way connects in with a history of action drawing, with action painting and so on. But to me it goes further, it is actually thinking about the act of drawing as creating a musical instrument. Not necessarily in terms of the sound of drawing but the way it has developed for me as a way of thinking about making sound. So all of these things they are important to each other in the same way that writing is very central to my practice and writing whether it be making notes in a notebook or writing a book is very bound up with how I think of these more visible audible actions such as giving a performance or making a record. I guess as I get older I try to strengthen connections in my life that maybe ten, twenty, thirty years ago were quite separate, quite discrete entities and bringing them together. It’s something to do with getting old definitely and asking difficult questions about why I do these things. I mean my life is complicated enough without getting involved in gardening and drawing. So why is there the necessity to do that? I ask myself the question “why do I keep buying these drawing materials?”, If every drawing I make I throw away. So you see there is a drive there to do something. And when I wrote my last book, Sinister Resonance, I used that book to explore the notion of silent media, the sound of silent media. So for example seventeenth century paintings and I think that in itself is very important. Although I didn’t connect it up with this more recent exploratory work suddenly it dawned on me, and this may seem stupidly obvious, all of that time looking at paintings and listening to them, even though they were silent, was a way to talk to that part of myself, that was somehow mute, on the subject of drawing and its relationship to making music.

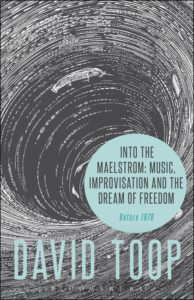

So it’s kind of a convoluted trail through my personal history really going back to when I was a small child really. Drawing and beginning to think about music and how they are connected up. Why they are connected up. And the final part of your question, how do I see that developing. I don’t like to talk about the future as a whole because we never know what’s going to happen, either to us or to the rest of the world. But there are certain areas of thinking I am doing, this drawing as musical instruments and also the idea of something I call organology without bodies. Which is a flipping around of Gilles Deleuze, well Deleuze got this stuff from Antonin Artaud‘s Bodies without Organs, it’s the idea of a musical instrument that has no object. It’s a subject that I have lectured on recently, it seems to connect with this idea of putting together a record of things that were very flimsy somehow. You know, you find a sound file and that goes together with another one and it goes together with part of another one and you make a mix of a few different things that weren’t meant to be mixed together and then a piece is developing. Then a melody I may have been playing on the guitar goes with that and all of this stuff is very tenuous. It is definitely not composition in that you are thinking of an idea; you know you have got a sound in your head, or a harmony in your head and you are putting it down through notation. It’s much more something that’s coming together from nothing or not very much. I think that actually has a strong connection with improvising in my life and I have got a new book that’s about to come out in a couple of weeks on improvisation. It’s called Into the Maelstrom. It’s the first of two volumes on improvisation, you know I have been improvising since I was nineteen and I regard that as being the source of a lot of what I do. It’s what helps me to write books, or what helps me to put together an album like this one. The fact that I can pull things out of nothing, or put things together which maybe shouldn’t go together because that’s what you do during any improvisation.

Innerversitysound: From your days in the Flying Lizards and appearing on top of the pops to your being a regular at Café Oto or touring obscure sound festivals. Can you describe the arc of your being in performance spaces and how it has evolved and what transpires for you in the act of performance now days and how it differs from your past in whatever sense?

David Toop: I was thinking about that today actually. I was playing a trio with Tanya Chan and John Lydecker at the Vortex in London. Strangely enough I have never played the Vortex and I have never met John before and I played with Tanya for the first time two weeks ago at Stewart Lee’s All Tomorrow’s Parties festival at a holiday camp in North Wales. I felt that ten years ago or twenty years ago I would have been very anxious in that situation. For all kinds of reasons, the first set a couple of things of mine were not working and it really didn’t bother me that much. It made me quite unsettled and then John was doing something where he was taking my signal and he was doing this kind of pitch following thing, so it was incredibly confusing, because everything I did was being thrown back at me, in a different form by what he did, so it was like a catastrophic identity loss, I just didn’t know what I was doing. And I just felt very comfortable with that, with all of it, you know the unfamiliarity of the venue, the people, the breakdown of equipment, the not knowing what I was doing. You get experience, you hope you get experience, that allows you to feel much more relaxed in this situation.

I feel much more free in performance than I have for a long time. Not worrying whether something is clumsily done or too harsh or doesn’t work in this situation. Partly because I think that, going back to this record, I had this idea that these soundfiles were like plants or living beings in some way, they had an organic nature, they were capable of growth, and putting them together felt very similar to the act of gardening. That I could grow something by putting them together. So this track where I play a melody on acoustic guitar over a piece that is totally unrelated and I just felt instinctively that they would go together. Maybe that’s the situation where you would put two contrasting plants together and watch them grow and see what happens. Some of its within your control and some of its not within your control. You just accept it, I am much more accepting, that’s the thing that I am trying to say, I am much more accepting now that I am older of what happens in performance and for me it’s a way to allow all of these different parts of my personality. Because I like quiet things, I like deep and delicate things. But I have a violent side, but by that I don’t mean that I would ever get into a fight or commit a violent act, but I recognise that it is there.

If I think about my taste in cinema for example, I watch quite a lot of violent films, and so inevitably you ask yourself questions about that: ‘what’s that about?’. I tend to think all human beings have violence within them. It’s just a question of what you do with it and whether you can use that productively or whether it is a destructive force that causes hurt and pain to others. Whether it develops into cruelty or whether it is somehow channelled. To me, I don’t think a performance is cathartic in any way, although it can allow you to articulate things that are otherwise unspeakable. It can allow you to release things from the body, which are trapped within for whatever reason. But I do think it allows you to become reconciled with these difficult parts of yourself. That in normal social communication, or in the way you present yourself to the world, are hidden. And it is sanctioned, in improvisation it is sanctioned if you are working with the right people. You can be violently noisy and it’s ok, because it is not about trying to kill the other person. So I think that working with these kind of anomalous elements in improvisation has really helped me think more deeply about the way I put a piece of music together. If I am working in the digital domain and thinking, ‘I am going to put together a finished piece here’, there is a crosstalk between the two activities all the time.

Innerversitysound: Spiritual practices, specifically shamanism and Buddhism have been pervasive within your musical production. The evolution of your interest is clearly of someone who has interacted directly with the cultures and has been deeply influenced. It does not come across as a form of ‘exotica’ or ‘orientalism’ but as a profound way of engaging with the world and how it influences your musical practice. Can you tell us a bit about how this side of life influences your musical interests?

David Toop: It’s not easy to talk about, I would say that. Partly because I don’t really know what the word spiritual means. It might not be a word I use myself, I am not criticising you here, far from it, there is an area of human consciousness and human need which gravitates towards the speculative. I am not a religious person, I should emphasise that, and I don’t follow anything people would call a spiritual path, but it is something that has always interested me and I have always thought there was a strong connection between that and the making of music. When I was very young, say in my early twenties, that’s when I got interested in shamanism. I guess I was thinking about whether music had to be a kind of entertainment. Was that it, was music just entertainment. Was it a consumer product or was there something deeper and at the time I was beginning to listen more and more to these different global musics, from Japan, Papua New Guinea, South America and Africa and so on. The relationship that I was discovering, the significance of those musics that I was discovering was very different from anything that I had really encountered up to that time. I was a church choir boy when I was young and I was kind of drawn to the ritual in that. I wasn’t drawn to becoming a Christian, I liked the singing, I liked being part of a group singing and I liked some of the rituals. So I suppose you could say there was some sort of origin in there that was of interest. Shamanism was of interest to me because the way sound was used, both instrumental sound and vocal sound was very central. Some of it was symbolic, the idea that someone beats a drum and the drum is symbolic of a kind of animal that carries them to another world and the sound of the drum could have a trance effect. Pieces of metal could be attached to the inside of the drum and clothing which would make a kind of random sound. That was interesting because I was interested in the freedom of free improvisation and the indeterminacy of contemporary composition, I was interested in accident and chance. So that had a connection and then the words to the songs were very poetic and expressive of this journey to another world and I thought – “well I wonder is it possible to do that” – in a contemporary setting.

We are so distanced from that world, we are so distanced from that reality, and everything we do is kind of an entertainment. I would say even the most extreme form of experimental music still has that slight taint of entertainment hanging to it. So how is it possible to create new rituals and inevitably that leads to study, anthropology and so on. Out of the study of music, through ethnomusicology, finding more about the foundations. So listening to say Tibetan liturgical music you go into its significance within Tibetan Buddhism. I am not a Buddhist by any means and I have got to say I am interested in the music, what the music can do, not the religion. What is happening in the music that is what I think transfers itself into my music. The question remains – what does music do for us? What is the point of it? What is the point of art at all? Very few people are able to give a very coherent answer to that. There are people who say that music is just kind of useless or it’s a mating ritual, or it’s purely a commercial thing. But if you go back through human history and you will find musical instruments from 30,000 years ago. And there is a profound need for music, or working with sound, and the way it connects to listening practice, the necessity of listening practice to survival and the way that translates into something that is far more elaborated through the creation of music technologies, musical instruments of different kinds and different voice styles and these extraordinary voice structures that grow up. Many of them died out in the twentieth century. But their forms are as diverse as the forms of any kind of natural form of animal species or plant species or whatever. So those questions are made for me and I think its more about searching all the time and asking these questions. Feeling the affect of music.

Innerversitysound: Your books, specifically Rap Attack #3, Ocean of Sound and Sinister Resonances have found appreciative readers in the Avant Garde sound world. Your style of writing seems to encapsulate this impulse that has been loosely described as Post Modern. Having no central narrative and being able to draw from all sources. Can you see that perhaps this sense of time, the dismissal of the materialism and scientific culture of modernism is coming to an end. That the reengagement with serious modernism is beginning again after this flirtatious period in the arts with spiritual nostalgia and multi-faceted identity?

David Toop: There was a book I liked a few years ago called Whatever happened to Modernism by Gabriel Josipovici and he was asking what has happened to this fantastic continuity of experimental literature and one of the interesting things I found out was he went back to Wordsworth and talked about how Wordsworth was an early modernist, which I was surprised about, but I was quite convinced by his argument. I have been going back through a lot of women writers, very innovative women writers, partly late 19th Century, early 20th Century, like Dorathy Richardson, Virginia Wolfe, even going back to Jane Austen. Finding early traces of stream of consciousness in her writing. That’s a very deep phenomenon that takes modernism back from being a strictly 20th century phenomenon. That takes it back to writers who are usually thought of as being a bit boring, classics, conservative and not very interesting. But as to changing, I don’t know, things are just so complex. So thinking in terms of single trends, which you have to do if you are suggesting that something is changing, seems to me to be almost impossible. There are so many currents going on in the world. Lots of them going in absolutely opposite directions. So you could convince yourself for a moment that something was a major trend, say music for example, but then you have a whole lot of other people in the world who think that music should be banned. I find it difficult to make those kind of assessments. Even within the world, my world, which is as restrictive as any individuals world is, even though I am involved in a number of different worlds and I travel a lot, I think of how many contradictions there are within that and how many disagreements there are within that. So I can only think about myself, about my colleagues and my friends and the people who I work with, the people who I encounter, the people with whom I have some sort of sympathetic relationship and I can ask “what’s going on with those people?”

Certainly I see something beyond the purely scientific. A good example of that is neurology, neurology is creeping now into improvisational studies. So you find these neurologists who are making these studies that ask – “where does improvisation happen?” But they don’t know anything about improvisation, most of what they come up with to my mind is useless. But it’s a big thing and they think if they keep going down that road they will find all the answers to these very complex phenomena like improvisation. I prefer to come to it from as many different angles as I can. Obviously as a practitioner and as a writer and as somebody who is interested in somebody else’s ideas. Gathering in ideas from different people which are often contradictory and I think creating decentred narratives, is something I have which I done in my writing since my second book. Maybe I did a little bit in the first book. Ocean of Sound certainly took that approach. I don’t know, I don’t have any easy answers to the question.

Innerversitysound: There is the sense of a non-narrative, non-linear aspect to your work. As if you are trying to access truth by the utter breakdown of structural representations. As if this strategy will afford you some type of deeper understanding of reality. By this strategy you build another temporary structure in which to inhabit. Is this our lot, we have absented ourselves from the idea of permanence and eternalism and now we have this ongoing building and moving project, modern nomadism. There seems to be a conflicting inclination here, of the desire for a sort of connection to a real world and simultaneously the embrace of a world beyond this conceptual idea.

David Toop: I am quite clear in my mind that I am creating worlds for myself to live in. So when I talk about pieces on this record for example, if you think about the title of the record, Entities, Inertias, Faint Beings, there are implications in that about what I am about with it. It’s about an engagement with the surfaces and substances of the world as I experience them, you know the thickness of things and the spatiality of things. The multiple perceptions of time and how you can use music to expand your notion of time. How you can use bioacoustics to expand your notion of time. So all of those things are real as far as I am concerned. Through creating this personal world, that’s how I intensify this relationship with the real. That is what modernism was about. You go back to these writers like Dorothy Richardson and James Joyce, Virginia Wolfe and Samuel Beckett; it’s all about unpicking this conventional reality and intensifying its relationship to its substance. You know to its sound and its smell and its taste and its touch and the impact it has on us. It seems to me that is all anybody has ever done.

I don’t suffer from any spiritual nostalgia. I don’t think that people understood the world better. Say the notion of infinity, it is impossible for a person to grasp, so you can read spiritual teachings on infinity, or view religious artwork on the subject, say tantric artwork, and in the end it’s no more convincing than the things that I come up with. The last thing I’m implying here is that I am some kind of spiritual teacher, because I am not. You have to create this world for yourself and that has to be meaningful in some way and that has to intensify this and make a kind of ongoing understanding. But you said ‘is that all that there is’, this sort of moving understanding. But I think that’s a huge thing. You know a lot of people their idea of the world becomes fixed when they are young and very little could come along to suggest that the world is any other way. I suppose in what I try to do, it’s the opposite of that. I am not saying that I am not susceptible to that, because I am, we all have feet of clay, but trying to unmake and remake and dismantle and create. Well let me give you an example, the conventional idea about sound is that it’s a throwing outwards and the conventional idea about listening is that it is a gathering in and that is one of the reasons why the ear is such a huge thematic element in sound studies. I have been trying to reverse this model and think about listening as something that goes outwards and meets the world and sound as a kind of gathering in, as something that draws in listening. I think you find this idea in Dorothy Richardson and Virginia Wolfe, these women who wrote a lot about listening and a lot about sound and a lot about silence and you find this idea. For me trying to reverse my thinking really takes me along way, it puts me in a different place, it unsettles my notions about something that is very central to me. Maybe it’s more important to me as I get older, for I am conscious that as you get older there is a tendency to become more fixed, you can get very conservative about certain things and get very complacent. I use a notebook on a regular basis and the notebook is really a way of constantly trying to unsettle my own ideas and out of that unsettling very often something will arise. So you will notice that the tracks on this record have mystifying or very extravagant titles. But they all come from notes made about photography or literature or lines I find in books and they relate somehow to some aspect of the piece.

David Toop performance White Cube January 2015 from Cromwell Films on Vimeo.

Innerversitysound: 2016 has already been a fruitful year with the release of Life on the Inside and now Entities, Inertias, Faint Beings. Are you going through a rather productive stage, do you have any idea of why this period has come about? What can we expect from you in the near future? Do we expect to see you touring soon?

David Toop: I do have an idea of how its come about, it’s a very personal thing in a way but its very much about the collapse of a life at a certain point four years ago and having to start again in a way. The situation that put me in unleashed a lot of energy, unleashed a lot of creative energy. I spent quite a lot of time alone and that allows you to work in a different way. That played a big part in it. I reached a point of time in my life of more confidence. That comes with age I guess. Time gets shorter as you get older. I am 67 in a week and a bit’s time so those days when you are in your thirties and you think that I will get around to it one day. Well you think that if I don’t get round to it now it may not happen. I suppose I have been given some recognition in the last few years in terms of academic life, being made a professor and so on, and I can’t deny that that had an effect on me giving me more confidence. Because I have always felt that I have operated outside the centre, rather marginal, peripheral and for quite a long time not really taken seriously. In fact I had dinner with some people earlier this evening and they were asking me about this and asking me when did you begin to feel that you got some recognition. Well around 1994-95, releasing an album called Buried Dreams with Max Eastley which got very good reviews and later releasing Ocean of Sound which got very good reviews. But at that time I was in my mid forties, so it is a long time to feel that you are not making any impression at all.

Recently I have felt less inhibited about what I do. I think this record is an expression of that this paralysis of thinking what’s the use of releasing a record in the 21st century? I don’t have to tell you of all the changes that have happened in terms of distribution, platforms and formats and so on. I talked to Lawrence English about this and he kind of convinced me that there was a point. Also some years ago I interviewed Scott Walker for Pitchfork. I really stopped doing interviews and that kind of journalism. But I had always wanted to meet Scott Walker, it was fine and we were finished he said – “well what are you doing”? I was a bit taken aback, Scott Walker is asking what am I doing, I was just overwhelmed by flattery. I said to him – “I don’t know about releasing music now, I can’t convince myself that it is a worthwhile thing to do”. He said to me – “it’s what we do”. He was absolutely right it is what we do, so if you don’t do it then there is a massive absence in your life and never mind the justification for doing it or not doing it, in terms of the industry or distribution or what have you. Or whether people are listening to CD’s anymore, or any of that stuff, it’s what we do and I thought it was a beautiful wonderfully simple response. What he was saying to me was just get on with it. So there is a certain disinhibition that came about recently for all sorts of reasons. Emotional reasons and age reasons and feeling that what have you got to lose? Also being true to yourself. I worked for ten years as a music critic, a music journalist, trying to pretend I wasn’t who I was and it’s disastrous. So I am just trying to do what I want to do now and feeling that it kind of doesn’t really matter if you humiliate yourself or you make a mistake or whatever. It’s all part of this overall search to try and achieve greater understanding and to find some sort of personal need, whatever that means.

Entities, Inertias, Faint Beings is available on preorder from Room 40