As a musician and a visual artist Sarah McEwan has produced work in a variety of mediums, as well as generating work in others through group exhibitions in the Riverina.

The two areas of sound and vision are joined in Her Riot, a solo vehicle for McEwan that is driven by a “Manifesto Against Evil: Music, Bands and Coolness”. This document is a critique of the musician lifestyle, well aware that it is a self-critique. In this way the vehicle carries a lot of baggage, and apparently the Greek origin of the word metaphor describes a cart, because the metaphor here is that McEwan is pushing her work away from the traditional music industry.

McEwan is a core member of The Cad Factory. The artist-run initiative is a partnership with her husband Vic, who was awarded the inaugural arts fellowship for NSW last year. Their musical project Grace Before Meals is one of many for Sarah in recent years.

She credits a Tumbleweed gig in 1992 as a formative experience. “The first band on was Dinky Crash and they were punk and outrageous and the singer wrote songs about artists and threw things at the audience. I thought I’d almost die. I couldn’t believe such a world existed and I just wanted to be a part of it. I became completely obsessed with underground music and culture from that point on.”

“I didn’t start playing drums until I was 21 and my friends and I formed a band. We were pretty terrible but I think that made us kind of endearing. Once I started playing drums, I almost totally forgot about art which I had studied at uni, and spent all my time practicing drums. I only really started to play very well when I was 30 and of course at that time I became pregnant and stopped playing gigs when I was 20 weeks. I played again for the next few years but living regionally, breastfeeding and touring became very hard.”

“Around this time my focus started to go back towards art and The Cad Factory; an artist run space that I had volunteered my time at since 2006. We started to work on some really fun and paid projects which led me in a different direction away from strictly focusing on bands.”

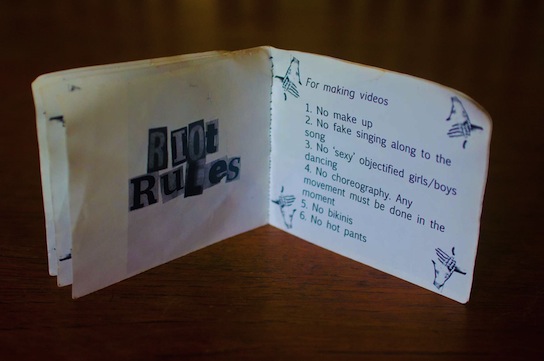

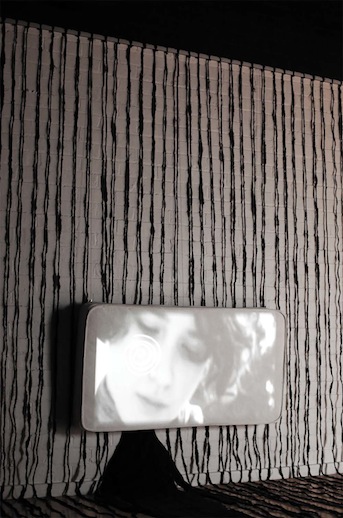

Her Riot is presented as a band albeit one that appears largely in exhibitions. Audiences watch film clips that accompany the music and reflect on the consumption of music as a product. In some ways it elevates the production of music from a commercial byproduct to an artistic one. In a copy of the Manifesto when work was presented at the Grong Grong Creative House project, rule number 24 is “Music video clips can go to hell.”

Her Riot has more recently been seen in Contemporary Australia at M16 Artspace in Canberra. It seems Her Riot music video clips go to art exhibitions.

Jason Richardson: How did this combination of your music and art come about?

Sarah McEwan: “Although I was completely obsessed with playing music, my world has always been framed through art theory and the ideas that are explored by different artists and cultural theorists. As a teenager I was always reading about visual artists but listening to music. I think the two go together really well. It’s only now that I’m older and wiser to the realities of both the art world and music world, that I can combine these elements in Her Riot with depth and meaning.”

“In 2006 I started volunteering my time at The Cad Factory which was an underground warehouse space in Marrickville. I really loved the ethos running through every aspect of the place and it felt really exciting to have a space where you could do what you wanted and really push underground culture. I love the idea that you can do everything yourself and I really learnt this at The Cad Factory and it made my skill set very broad.”

“This same kind of philosophy is running through Her Riot; you can do what you want, have your voice and challenge dominate ideas about culture and the way you consume it.”

Jason Richardson: Does your experience of being a drummer share similarities with art-making in realising ideas collaboratively?

Sarah McEwan: “Yes, most definitely. Playing drums in a band means you need to understand what everyone is doing by listening intently and figure out what beat holds it all together. It’s very similar to collaborations in art making where you are working together to achieve a common outcome. You need to listen intently and understand what the other person is thinking and doing.”

Jason Richardson: What led you to develop that process? How has it been implemented? Did you have to revise aspects to make it work?

Sarah McEwan: “My 20’s was all about going out, seeing bands, practicing music and hanging out. In this time, I was ever so slowly digesting the cultural theory I had studied and was reading and seeing the real life applications of this playing out. My particular interest has always been feminism and I observed my lived experience with detached fascination, not really knowing how to negotiate it all.”

“During this time I encountered a steady rate of sexism. I have many ‘war’ stories but probably the worst and most shocking experience I had was a gig at the Annandale Hotel in about 2005. Our friends band was headlining and it was their album launch, so we were on before them. While we were playing the lighting guy dropped all the lights on stage and shone a spotlight on my breasts. Everything was black except my breasts. At the end of the song the three guys in the band who I played with, were upset and started yelling at the lighting guy. It didn’t deter him and he kept doing it for the next couple of songs. I was very rattled afterwards and was so angry. And you know what, that arsehole won because he had put me off so much that I never said a thing to him. Luckily one of my friends did.”

“Along with gender issues, the other striking aspect I observed in this time was the chase to make it as a musician and the whole superficial baggage that goes along with it. I had friends in all different stages of their music careers and again I found it fascinating watching them negotiate this space. I saw exactly how far they were willing to bend to be successful and what they had to do. In this process no one ever stopped to reflect upon who their authentic self was and the signifiers they are giving out about what ideologies they are representing.”

“It took me years of thinking this over before I finally developed Her Riot in its complete form based on feminism and ideas around authentic representation. To begin with I wrote an extremely provocative Manifesto Against Evil, Bands and Coolness. Then a set of rules for making video clips. Her Riot is my ‘anti-band’; it functions as a band, but critiques the structures that are in play when you are in a band.”

“It’s the initial stages at the moment, so no revisions just yet. It is a slow process for me as I write the songs, play drums, piano and sing, then shoot and edit the video, make a little zine and then create an installation around all these elements.”

Jason Richardson: It’s often observed that there’s a shortage of women making music. Do you have a view on why they choose not to get involved?

Sarah McEwan: “It is undeniable that women are under represented in male dominated areas. I think of this as an historical gap that will hopefully close over time in the Western world. It has only been in the last 100 years that women have been pushing for equality and in the last 30 years that there has been some real gains and challenges to traditional roles. Men have had 1000’s of years participating in every aspect of life so the gap is very wide.”

“I have always felt there is a bit of a boys club when it comes to music. Sometimes I felt it in an extreme way, and sometimes not at all, depending on who I was around. When I felt aware of my gender it had this horrible way of shrinking me and I felt silenced by the patriarchy, that being a girl gave me no authority. And I have heard men belittle female musicians and I have been belittled by male drummers.”

“I actually think that men need to do a lot more self evaluation of their own internal workings, musicians or not, to understand where their sexism comes from and to really shake out of themselves their own assumed privilege and work on changing their own language and actions if their is ever to be some resemblance of equality.”

“In terms of the career path you take that seems very personal. I spent so many years of my life infatuated with underground live music that I would never have predicted that I would start an anti-band critiquing the very thing I loved and not playing live music!”

Jason Richardson: Maybe a bit of comparison about art and music scenes? I like Eno’s thoughts on a lot of subjects, including this.

Sarah McEwan: “This was very interesting to read. But I feel like it has no relevance in my life in a way. It is an interview with two extremely high profile, older men artists who live in a completely different way to me. That is their experience and mine is totally different. It’s a classic case of old white men having authority on a subject that I find hard to relate too.”

“I’ve never been interested in succeeding in a mainstream way; exhibiting at the right galleries, playing with the right bands or aligning myself with the right people to ensure my sense of self is valorised by the right people. My lived experience has been to work in systems that subvert those very notions and structures that place capital before people.”

For more information on Sarah McEwan check her website.