The bass already sounds as if it was coming from elsewhere. Huge but muffled, spread out at the very bottom of the frequency as if it were bleeding through from the other side of a wall. Distance. And then the vocal kicks in, writhing against the syncopation of the drums to its own rhythm. There’s no placing it.

Erase that. Let’s make it vocals, plural, because there’s no way we can talk about this music in terms of a singer, a person, a whole. It’s a plethora of voices wrapped around nothing but itself, a kind of architecture and a schizophrenia at once, pitches shifting, layers in the mix held out like staircases that disappear as soon as you put a foot down. ‘Holding you / Let it be alone / Let it be alone / Let it be alone’ – the invocation rings out three times, a trinity, and that might be what it says, or it might not, it’s hard to tell. Whatever, it’s the loneliest prayer in the world, a call-and-response with nowhere to go, no one to sing out to but itself, selves. Not male, not female, and certainly not human, but instead, the remnants of tuning rapidly through stations up and down the dial, brief snatches of voice released into the atmosphere. Forming a cloud above the city, a shimmering, spectral haze.

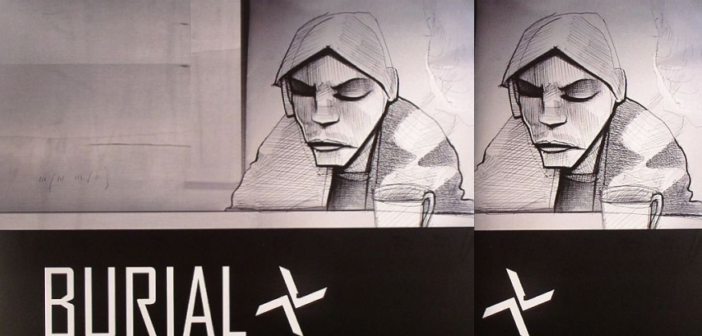

Welcome to ‘Archangel’, the second track on the second Burial album, Untrue. It’s a pop song that hasn’t been invented yet.

Delighted giggles. “What I wanted is to get people singing: girls singing and pitching them down, so it sounds more like a boy singing, and then guys singing, and pitching them up, trying to get them a little more female. You get this weird middle ground and I’m into that.”

Burial is talking down the telephone line, a disembodied voice on the other side of the world. It’s a lovely voice, actually. Softly spoken, South London accent, hugely expressive. Pauses, inflections. The more important the topic at hand the softer the voice gets, causing you to lean in, or jam the phone closer up against your ear.

“I like a speed in the tunes halfway between a sway and a pulse,” he says, describing the new record, “and there’ something about that speed, with a vocal where you can’t tell if it’s a boy or a girl, where it’s more like a ghost singing on your behalf. Or like a voice that’s trying to tell you something. Where the source of the song is hidden – I feel a bit stupid saying this but I think it sounds sexy, basically. That’s what I’m trying to say.”

Untrue is a record with desire streaked across it, and at times an almost unbearable yearning, but neither the desire nor its object is ever fixed, not for a moment. It’s this that makes the record both beautiful and hugely disconcerting, for desire here is not a place of safety, not a retreat into or towards a recognisable human body, let alone a female one. Untrue is post-human, disorientating.

“Sometimes there’s a main vocal and then another layer where the singing is totally out of reach. It’s like an air duct in the tune. There’s all this sound, so no matter how deep down you look into the tune there’ singing at every level, until it’s too dark to hear it.”

“There’s a Playstation game called Forbidden Siren,” he continues, “I’m always well moody at it for thinking of that name first, because I can’t use it! Well, I can,” – you can almost hear him smiling – “I think I might just use it anyway, but it doesn’t sound so good, “cos I blatantly stole it off of a game. I love that phrase because a siren is this thing – I thought it was just a siren on a police car or whatever, but I found out – it’s like a girl singing, but far away. You just hear it carried on the air and you’re drawn towards it. I fucking love that. I don’t want a singer, you know, I don’t want a vocalist. I actually want it to sound like I’ve got one of these things singing in my tunes: a siren, or something not human that I’ve got chained up in the yard. And that might sound pretentious as fuck, but I don’t mean it to be. To have that kind of longing to be taken away, or like something from the past. Something more scary, outside of yourself, that’s trying to draw you away from the world.”

Away from the world. It’s something that Burial knows about, living in what he describes as “exile”. He’ distanced himself from congratulations and acclaim, from the pressure of having released an album last year, his first, which comprehensively punched through any walls that were left between South London’s tight dubstep community and the rest of the globe, hopping locations and infecting listeners and already lauded as one of the albums of the decade. Most of all, he has distanced himself from recognisability – there are still only a small handful of people that know who he is. He’s still living in South London, sitting on the rooftop of his building with its view across the city.

“If I had my way I’d never cross the river,” he says. “London’s weird, it’s home, but sometimes you’re walking along and it’s deserted. You can turn a corner and there’s no one. Sometimes you’re in a place where it’s not even designed for people: you’ll be standing in the middle of a fucking motorway and there’ not even a pavement, and then you get across and there’s a fence that you can’t get past. You’ll find yourself in a weird car park with no cars in it, where there’s no way out, nothing. It’s odd.”

Some might see Burial himself as odd, for refusing to inhabit, to embody, his underground fame, as if the evasion were disingenuous, part of some clever plot. The contemporary world is so hooked on the pleasures of profiling and the pursuit of obsessively documenting oneself – the more instant, the better – that to not do so strikes many as suspicious, untrustworthy. If you’ve done nothing wrong you should have nothing to hide, goes the mantra, nothing to be afraid of. But hiddenness and disappearance can have their own liberations.

“I’m just not that kind of person, I wish I was, but I’m not somebody who can step up,” he explains. Burial’s absence is, of course, part of what makes his music so potent. People across the world connected with last year’s (self?)-titled album precisely because the spaces called up by the music were so very architectural; evacuated of human presence. Burial was an intoxicatingly dark, sparse record, the subaqueous bass at its core like the pulse of buildings past midnight, or perhaps their echo, heard as you passed through the gap between one tower and the next.

“I’m sort of nocturnal,” Burial admits. “Often I’ll make tunes, and then I’ll go out, or I’ll think of somewhere that I can walk to, maybe at 3am, and then I don’t listen to the tune again. Sometimes I’ll walk around and dream up a tune, and go back and make it, late at night. It’s not about “testing’ to make sure that technically it’s good, because my tunes aren’t technically good. But when you’re playing a tune at night and just driving around empty streets, going around London, if your tune sounds right” – he breaks off, dovetailing into the next thought. “They’re quite specifically for London, but it’s really buzzing for me if I hear about someone in another part of the world that’s into them, it’s nice to hear.”

There were faint glimmers of comfort inside of Burial, particularly in the hiss and crackle that was traced through every track, but frankly, it was a terrifying album, its perspective so deep that it felt like looking into an abyss. “You’ll be walking around somewhere indoors, uninhabited,” he describes, calling up architecture, “and I love the sound of that, the sound of your trainers on the floor in an old hospital, that kind of squeak. Or some dark place that’ll have a lift shaft that you don’t want to go anywhere near, but you drop something down in the dark and you get this weird echo that goes far away from you. You get this evil sense of space when there’s no one there, and I’d do anything to get that in my tunes.”

There would have been an understandable logic in continuing down this dark sonic path, in paring back even further, almost to nothing. “The record I was going to release was going to be totally dark – I was going to go all out and make the darkest record ever, because I was feeling like that” he offers. “But then I realised that the last thing you do when you’re feeling like that is to make a dark record. You make something to cheer yourself up.”

Untrue was put together in only two weeks. “I was just like “Fuck it, I’m going to do these tunes in ten minutes,’ and then I’d spend a bit more time on the details. It just happened really fast. Basically I felt a kind of pressure around me, and I just wanted to make something that was like – I don’t know what that word is – naive? Back to how it was when I first started making tunes, and the only people I could play them to were my brothers and my mum. I’ll save the really – not the ambitious stuff, but the stuff where I’ll spend ages on it – I’ll save that stuff for later.” Though he has assiduously avoided reading his own reviews, he knows that some listeners will be expecting a record that is “maybe more sophisticated or technical. I’m aware of what that music is, but I can’t make it yet.”

Untrue takes the glimmers that speckled Burial and enlarges them into a glow, one that dissipates and then returns, track after track. The pitch-shifts on “Endorphin’ and “Etched Headplate’ – where vocals are stretched into wordless, luminescent textures – are like the wash of lights across an evening cityscape. If the key element of Burial was concrete, then Untrue is halogen, gaseous.

“In this new one I was obsessed with making it glow a bit more, and having these little clips of vocals, and tiny moments of warmth for a split-second, and then it would go, it would fade out.”

“I love that kind of thing where you’re out in the cold and you almost want to be kept out in the cold,” he says, speaking in a hush now. “You don’t want to be let back in. Sometimes when you’re in the cold you’ll get this kind of shiver go through you? Like something nonhuman tries to comfort you.”

“The tunes are personal, but I want them to mean something to someone, not just someone into it in a social kind of way. I’m not really into that. I know what it is to make tunes that a bunch of lads can tear around town to in a car, but for this one I didn’t want to make that. I wanted to make something that was kind of half-boy, half-girl. That’s part of underground music just as much as a heavy bassline.”

The voices on Untrue aren’ sweet; they have little, if any, of the orgasmic drive – upwards, upwards, upwards – of 2step or jungle vocals. They dive and twist, winding through pitches with massive anxiety, with lingering sadness. Emotion and production are locked together: you can hear the blips and gaps between samples, the voices unable to animate themselves, to achieve release from the tune.

“I do fuck with the pitches,” he explains, “but I don’t understand things being in key. That’s why I like that air-duct noise, like a presence in the air. A kind of rush, like the ghost of a sound. I take all my keys from that note, almost like a banshee, like you were hearing a strange, wounded animal cry. The sounds are more a part of that, like when someone calls you in the middle of the night and your ringtone sounds scary for a second. I like those kinds of noises that make you feel odd. You leave yourself when you hear them.”

Odd is a key sensation in the Burial project. This is music perpetually in search of a centre that never was, and perhaps never could be; a mourning for both self and collective identity. It is not music that is in flight from the technologically mediated human being, but rather, music that (re)remembers the rave, in particular, as a site of technology (within the overlooked warehouse, or the field at the edge of the motorway) where a new kind of self might have been made, filtered through the sound system, dissolved and reconstructed within the mass; shifting, euphoric, temporary. Perhaps even more so than its predecessor, the glow of Untrue is the afterglow of rave’ history.

“I was brought up with a lot of rave tunes and hardcore tunes,” Burial remembers, “and people telling me stories, like folklore. When I was really little, older people would be telling me stories about where they’d been, playing tunes. They’d been to these clubs and they’d drive through the night to get to these parties. But I wouldn’t know anything about it, because I’m too young to have ever gone to anything like that. It was almost this euphoric thing back then, but I find it really sad to listen to now.” It’s hard, here on the flat page, to capture the tone of his voice as he goes on, but there’ a breathlessness to it that holds the faintest trace of urgency. Reverence. Longing. “I love those hardcore and rave tunes because they sound deep, hopeful, for the times, and the people. Something big like “Papua New Guinea’ by Future Sound Of London, ‘We are E’, or old Prodigy tunes. Anything from that time, old hardcore tunes and jungle tunes. It’s unbelievable, that glow in the tunes, it almost breaks your heart. I’ve been around people when a tune has been put on and they’ve just broken down and cried. They’re reminded of a time. I feel like that when I hear tunes like ‘The Chopper’ by DJ Hype, or ‘Angel’ by Goldie, Danny Breaks, Ed Rush tunes. I think the hope you have when you’re young is destined to die, but I don’t want to believe that.”

Hope, of course, is never passive, never simply about looking back. Hope is not a longing for a past that never was. It’s a way of imagining a future that will be inscribed by the past, a way of making history, of continuing it. Hope is the opposite of nostalgia.

“I see so much hope in those tunes, even the darkest of those tunes, jungle tunes and all that. In the UK – “cos that’s all I know – those tunes tried to unite people. I want to let those people know that they didn’t fail. Because to some people, those tunes mean everything. I almost feel that if ravers who are a bit older could hear a bit of that in my tunes, I could die happy.”

“Dream life’, wobbles a vocal line on “Raver’, Untrue‘ closing track, “When the world seemed / Easy’. At least, that’s what I hear. “My dream would be to make a record where you thought you heard the lyrics, but the next time you heard it, it didn’t say that at all.”

Songs that are out of reach, or that never quite were; dreams of perfection; form part of Burial’s hearing. Loss activates the imagination. “I liked the days when you’d hear a record and you didn’t even know who made it. There’d be nothing written on the white label. It might sound like Source Direct, but I’d never know. I’d stay up all night listening to the pirate stations, hoping that they’d tell me what that tune was three hours before, and they never did. And maybe you never heard it again. Or maybe you tried to record it and the tape went wrong, and it’s gone. The atmosphere in those songs; it was a miracle that you ever got to hear them.”

Fittingly then, the musical elements of Untrue are always receding, or moving off-centre; always in danger of being erased. Part of Burial‘ radicalism – particularly within the field of dubstep, where the crisp beat rules – was the way in which the rhythms were eroded by crackle – rain, fire, vinyl hiss and static. It felt like the record was breaking down from the inside, like maybe the more times you played it the more decayed it would become, until it was reduced to mere stutters, ticks. Untrue keeps the crackle, but it uses those maddening, dizzying vocal layers as a way of destabilising everything else. “I half-liked Untrue [as a title]because it sounded like some old UK garage tune, but also it’s like when someone’s not acting like themselves. They’re off-key, something’s wrong, an atmosphere has entered the room.”

The new record tilts between strangeness and a kind of desolate safety, if the latter is not a contradiction in terms. Perhaps vulnerability is the word. It’s the comfort of leaving comfort behind, of feeling sad and alone in the city, passing doorways and overhearing other people’ stereo systems, on the periphery of shared living. Burial’s music presupposes this atomised, drifting audience, scattered through the streets.

“I think that whatever time you have when you’re out, you can have a mad time trying to get back home, walking across the city late. Or in a mini-cab, watching your city go past the windows, and you’re feeling jumpy, like the music’s still in your bloodstream. I want to make music for that time.

“I love those old Sam Cooke tunes,” he says later. “He’ll be singing a happy song about having a party, but something in his voice gives away that he’s not happy at all, he’ sad. He’s singing about the last party. If I made my dream album it would be the kind of tunes that you’d put on if you were having the last party on earth.”

Enervated divas and crooners, the trace of soul music’ celebration but also its melancholy; the sassy sheen of contemporary r’n’b scratched over and submerged – these things form Untrue‘ uneven pulse. Listen to “Homeless’, where snatches of the phrase “Oh Lord’ reverberate into the deep like a drowned choir. The embrace of this music, the emotion of it, is brave. Doubly brave because the embrace does not offer a sense of belonging or return; Burial’ music has no oneness, so sense of shelter or security. What it offers is doubt, and that doubt is radical, propulsive, a way to keep living. Doubt is counter-posed to brooding; doubt is open where brooding turns back in on itself. This music has many points of entry, it fizzes and floats and escapes, with no centre to organise itself around, nothing to act as an anchor.

“I understand that vibe, of wanting to make that darkside stuff, something malevolent.” says Burial, gently. “That violent, brooding thing, I know it; I grew up on those tunes, and someday I’ll make a whole album of them. But I just think it would be nice to do something that was not like that. To do something where the threat was always there, but it’s the last thing you want to think about.”

“Sometimes you’ll go to a club, and before you go in you can hear it through the walls, and you put real life away from you. But I’ve seen people where they’ll be upset, or there’s a girl crying next to the bar – they’re twisted up about something but it’s almost like they make that decision to walk back inside. There are things going on there, and you can get to that sometimes in the music. It’s not just about some massive drop in the tune, or some massive bassline that comes in, it’s something else. Sometimes people go out to forget – most times you’re happy, devil may care – but sometimes you go out because you’ve got all your life on your mind.”

Burial’s Untrue is available from Hyperdub/Shogun.